Scuba diving with oceanic whitetips should be on every diver’s bucket list. What are these sharks like, and what’s the best place to potentially spot them?

Taxonomy of an oceanic whitetip

Oceanic whitetip sharks (Carcharhinus longimanus) are large, pelagic requiem sharks. This means they are migratory, live-bearing sharks that live in tropical and warm temperate seas. They swim at the surface and down to a depth of 500 feet (150 m). This stocky shark’s most distinctive features are its long, white-tipped, rounded fins. The first dorsal fin is distinctively large and rounded, and the paddle-like pectoral fins are very long and wide. The shark mates during the early summer in the northwestern Atlantic and the southwestern Indian Ocean. As viviparous reproducers, females give birth to between one and 14 live pups after a gestation period of 10 to 12 months. The oceanic whitetip’s diet primarily consists of bony fish such as tuna and mackerel, but also includes stingrays, sea turtles, sea birds, squid and crustaceans.

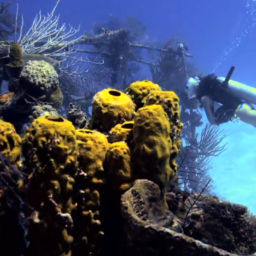

Diving with oceanic whitetips on Cat Island

It is the migrating tuna that attract oceanic whitetips to Cat Island in the Bahamas. The island sits right at the edge of the continental shelf, bringing the deep waters of the Atlantic close to shore. Depleted in much of their range, the oceanic whitetip population of the outer Bahamian islands is still thriving, making this a unique and rare encounter. About 10 years ago, Stuart Cove’s Dive Bahamas and a few other operators started to notice that the sharks were attracted to local fishing boats to steal the catches. Since then Stuart Cove’s has been running charters to see the sharks in April and May, when both the sharks and sport fishermen are there to land a big catch. The species is usually solitary, but individuals congregate around Cat Island when food is plentiful.

How the dives work

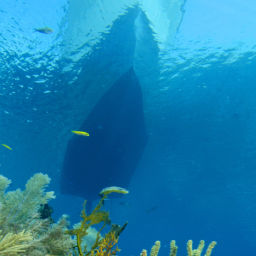

Boats attract the sharks by throwing dead fish into the water…and then waiting. On a quest to see oceanic whitetips, having a lot of patience helps. Like other sharks, the oceanic whitetip has a great sense of smell and will come check out the bait. The first sign of arrival is the distinctive white dorsal fin popping out of the water. The sharks are quite stocky and can grow up to 13 feet (4 m). The ones around Cat Island, however, are commonly around 8 to 10 feet (2.5 to 3 m) long.

The sharks hang out just under the surface and down to about 40 feet (12 m). With the clear, blue water and amazing viz, the sharks look spectacular. Remoras and pilot fish often accompany the sharks, which makes for even better photos. Caribbean reef sharks often join the fun, and then you’ll really notice the size difference between the two species.

Whomever you dive with, please remember that it’s always important to listen closely to recommendations and safety briefings when diving with these sharks. Get to know local regulations and protocols. Safety for both you and the sharks is paramount to allowing continued interactions in the future.

Protecting oceanic whitetips

Once, oceanic whitetips were among the most prolific pelagic sharks on the planet. Sadly, numbers have drastically fallen. Humans have caught them in large numbers virtually everywhere they occur, particularly in pelagic longline and drift-net fisheries. Fins are in high demand and prized on the international market. They are listed on IUCN as Vulnerable Worldwide and Critically Endangered in the Northwest and Western Central Atlantic because of the enormous decline, shockingly in some areas by up to 90 percent. CITES has added them to Appendix II to try to bring some regulation and licensing to the trade in their fins.

Since 2011, the Bahamas has outlawed killing or trading of any shark, so the waters are safe for the oceanic whitetip and many other species. But the sharks travel huge distances and, once they leave the Bahamas, other country’s fishing vessels catch them easily. It is vital as a scuba diver to seek out shark-diving destinations and to support shark tourism. Governments can then realize the millions of dollars to be made from this industry, rather than letting sharks be killed, which will only ultimately hurt both the fishing industry and the ecosystem.