On the last dive of a trip in the Maldives, I was sucked down deep by a whirlpool, with my safety sausage wrapped tightly around my legs tying them together so I couldn’t swim. I thought I was going to die, but I survived without physical trauma. A few months later, I was excited when I splashed down on my next dive—until I panicked deep underwater. I’d never experienced a panic attack before in my life and had always felt comfortable in the water. It took a lot of work before I adored diving again.Panicking during a dive can happen to anyone, but if it’s something that continues to reoccur, you need a plan for overcoming dive panic.

Avoidance only worsens the problem and unchecked panic during a dive can result in injury, or even death. Check out the detailed plan below with techniques compiled with the help of a psychologist.

Note: Do not use this article as a substitute for medical, psychological, or dive instructor advice, or as a guide to get back into the water before you’re ready.

Understand the problem

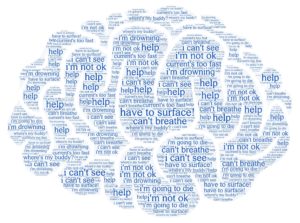

Panic is both a biological and a psychological response to what the body perceives as a life or death situation. Physically, your breathing rate often initially increases, and you’ll feel a strong urge to inhale. Your heart rate increases, and faster, shallow breaths build up carbon dioxide (CO2) in your system. These physical processes can convince the brain that something bad is occurring. The brain then increases the reaction, sending out stress hormones and convincing your lungs and heart to work even harder. This can turn into a vicious cycle, spiraling into a panic response made even worse since you know that fast breathing can deplete your tank and panic can kill divers.

First, figure out what triggered your panic attack. Some common triggers include:

- A prior dive accident/incident you experienced or witnessed

- A situation/environment you faced for the first time (e.g., low visibility, fast current, cold water, etc.)

- New or different equipment (e.g., different fins, heavier weight, thicker neoprene, etc.)

- Ill-fitting equipment

- Equipment that feels restrictive

- Too much gear

- The physical shock of cold water

- Overexertion

- Stress in your life built up to a critical level

- Lack of sleep

- A combination of the above

Recognizing what caused the initial panic can mitigate the problem in the future.

Increase your confidence with repeated, easy dives

Every time you experience a bad dive, it increases your panic response. Build up your confidence with repeated easy dives where you feel safe to help overcome the previous trauma.

- Dive in a pool or start with easy dives in shallow water, preferably with good visibility and no current. Dive when relaxed and well-rested to ensure a good experience.

- Slow things down and dive at your own pace.

- Dive with someone you trust and not with a group.

- Don’t increase the difficulty of your dives until you’ve completed many dives successfully without even a hint of panic.

Dive with a supportive instructor or DM

Hire a well-trained and supportive instructor/DM to dive alone with you—not as a course or a group dive. You may not be able to dive as often, but fewer successful dives are better than lots of dives with a higher chance of an issue.

Talk honestly with the instructor/DM about your panic and agree on how they can help you underwater detailing all the specifics. For example:

- Should they touch you or not during the dive or a panic attack? Some people prefer their hand held. Sometimes, touch feels more claustrophobic.

- How close should they stay during the dive or a panic attack? Some people desire someone next to them. Others prefer no one invade their personal space.

- Should they signal you during the dive or a panic attack? Repeatedly questioning if you’re ok can increase anxiety. During a panic attack, the person calmly performing the “slow down” hand signal timed with exaggerated slow breathing may be more helpful.

Don’t rush diving down

Enter the water, but remain on the surface and calm yourself for a few minutes before you descend. There’s no harm in ever telling a buddy or your instructor/DM that you need time to compose yourself before diving.

Then, slowly descend with no rush. Remain extremely shallow for a while if it feels safer to you or descend in stages, dropping down a few feet at a time while holding onto a line.

Dive with solid equipment

Your equipment impacts how you feel on a dive:

- Only dive with regularly-serviced equipment you know you can count on.

- Avoid ill-fitting equipment. A tight suit feels claustrophobic whereas a loose suit won’t maintain good warmth. A leaky or fog-prone mask can restrict your sight. Even if you can’t afford a full dive kit, purchasing a mask, fins, and wet suit that all fit perfectly can mitigate many problems.

- New equipment—even just a new pair of fins—feels uncomfortable. Test it out in a pool first.

- Hoods can feel restrictive around your throat. Instead, wear a dive cap or beanie with an adjustable strap for iwarmth with less constriction.

- Don’t dive with any unnecessary equipment while you’re working through your issues (e.g., a camera, a lift bag, etc.).

- Don’t dive with equipment that’s even slightly problematic on the surface—it doesn’t get better underwater.

- Ensure you’re diving with the correct amount of weight. Too much and you’ll feel like you’re being dragged down. Too little and you’ll fight floating to the surface. Perform a weight/buoyancy check before diving.

Adjust for narcosis

If you’re deeper than 100 feet (30 meters) and feel panicky, ascend to a shallower depth at a safe rate to avoid the complication of nitrogen narcosis.

Mitigate cold-water shock

Cold shock is the physiological response to sudden cold, especially immersion in cold water. Cold-water shock increases your breathing rate and can spiral you down into a panic response. Wearing heavier weight, more equipment, or a thicker wet suit can feel far more restrictive. Minimize these issues during a dive by first jumping into the water without equipment, aside from the barest essentials like your suit, mask, fins, and hood. Swim around.

Once you feel comfortable, remove your mask and place your face fully in the water for a little bit to accelerate the adjustment. All air-breathing mammals possess the “mammalian diving reflex,” a physiological response triggered by cold water hitting the face. The reflex slows the heart rate and constricts blood vessels, which can affect breathing. Adjust for this before you dive to ensure you’re not gulping for air as you descend.

Note: If you’re diving in a wetsuit, then flood it by actively separating the suit’s neck from your body. Flood water into your hood/beanie. Then, wiggle around until you feel the cold water spread everywhere. This forces your body to heat that water up, kicking off the adaptation process. It also loosens up the thick wetsuit, relieving that constricted feeling. Once you’ve adjusted to the cold water and feel relaxed with easy breathing, then don the rest of your equipment to dive.

Prevent overheating

Feeling hot before a dive increases feelings of suffocation. Prevent overheating on land with the following methods:

- Reduce the amount of time you’re geared up.

- Prevent overexertion by finding easier ways to slip on a suit (e.g., use a dive skin under a wetsuit).

- Leave the top of your suit down around your waist until the last minute.

- Pour water inside your wet suit. If you’re in a dry suit, pour water on your head.

Practice techniques to deal with panic

Ending a dive prematurely due to panic only solidifies your body/mind’s association that dives equal panic-inducing situations. Instead, try helping your brain and body deal with panic by practicing the methods below on land first.

- Recognize that you’re having a panic attack, that you’re ok, and that you can disrupt the panic response cycle.

- Utilize deep, diaphragmatic breathing. A slow inhale, and a slow and even fuller exhale will signal to your brain and body that everything’s fine. This will force your body to relax and combat the physical stress response. Your breathing urges are driven by excessive CO2, not by a lack of oxygen. Ridding yourself of the CO2 with those deep exhales relieves the out-of-breath distress.

- If it’s safe, stop swimming and relax your body in the water.

- Recite a simple mantra internally and repeat it slowly (e.g., “I’m ok” or “I am calm” or “breathe in; breathe out”).

- Focus on a single object that isn’t moving and consciously note everything about it. Something on your gear or your own body you can easily examine like your hand works well. Become as detailed as possible with your observations to distract yourself from focusing on your panic. For example: Cuticles require trimming, cuticle on thumb is fairly short, nails are filed into an oval shape, etc.

- Practice mindfulness to ground you in the reality around you. Focus on all the familiar physical sensations, such as how your hands feel clasping each other or how your arms feel during a dive, how your fingers feel touching your dive watch, how the water feels on your skin, etc. All of these specific sensations keep you in the moment and focus you on something objective.

- Use muscle relaxation techniques.

- If all else fails, swim a little shallower ascending at a safe rate without surfacing. This can help you feel near enough to surface easily but allow you to push through the panic during the dive. The more often you can process panic underwater, the easier all of this will become.

Determine what may help long-term

Figure out how to feel safer long-term. Don’t take a dive course or make major changes while still working through your panic. Instead, keep these thoughts as a part of a future plan. For example:

- Secure a back-up source of air — not one of those mini tanks with little air for an emergency, but a pony bottle or a full-size second tank to feel more at ease. Train with it first in a pool before diving.

- Take a self-reliant/solo diving course — not to solo dive, but so you can self-rescue.

- Only dive with trusted buddies or a DM/instructor, and not insta-buddies.

- Swap your gear: For instance, your fins may not mesh well with the type of kicks you prefer. Maybe a different style of BCD (or a backplate and wing) would better fit the way you dive. If you’re diving in cold water with a thick wetsuit, perhaps a drysuit class is in store.

- Evaluate your diving with a skilled instructor: Your buoyancy skills, your trim, and your kicks can affect how much you push your body during a dive. Practice an instructor to dramatically improve your diving and reduce your overall air consumption rate.

Secure professional help

Sometimes, the best way to address a traumatic experience or recurring panic is to secure professional support for the anxiety related to the event(s). You may want to enlist a professional to walk you through the techniques to deal with panic — and help you get back in the water confidently once and for all.

Note: Perform due diligence and choose a trained and licensed professional with experience in treating panic. If you live in the United States, search using the Psychologist Locator from the American Psychological Association including “panic” as the keyword under practice area. Most psychologists will offer you a free 15-minute introductory call where you can pepper them with questions and see if you click. You may have to attend multiple intro calls or even full-on sessions with different psychologists until you determine the perfect professional for you, but the right person can calm your world.