For a brief moment there’s a disconnect in my mind. I’m dropping down a descent line toward the wreck of the World War II freighter, SS Lord Strathcona near Bell Island in Conception Bay, Newfoundland. Even encased in a drysuit, I can tell how cold the water is — around 38 F (3 C). But as the outline of the wreck appears, for a brief moment it’s as if I’m descending on a tropical reef. Though I’m approaching 70 feet (21 m), sunlight dapples the superstructure of the wreck, creating a blaze of colors. White, orange and gold sea anemones crowd to find room; deep purple sea stars dot the wreck; and pink lion’s mane jellyfish float serenely among the ship’s cranes and broken spars. This is nothing like I’d imagined North Atlantic diving in the Bell Island wrecks would be.

History of the Bell Island Wrecks

When I first set out to explore the Bell Island wrecks, I’d expected strong currents, low visibility and cold water. But I knew this was the price to pay for a chance to explore the remains of two of the most infamous U-boat attacks in Canadian waters.

It was a moonless night on September 4, 1942, when U-513 crept into the convoy anchorage in Conception Bay. Like part of a plot from a Hollywood war movie, U-513 tucked itself under the stern of the SS Evelyn B and trailed it in to harbor. Ships came here for the ore extracted from Bell Island’s iron mines, crucial for making steel and thusly for the war effort. And so the German U-boats came for them.

U-513 Captain Rolf Ruggeberg waited until morning to begin his attack. He targeted the SS Saganaga and fired twice. Both torpedoes hit amidships. Filled with iron ore, it went down in minutes. Ruggeberg selected another target, but as U-513 maneuvered to get into position, the intended target, the SS Lord Strathcona, swung around and hit the U-boat’s conning tower. Though slightly damaged and forced to the bottom, U-513 recovered quickly. It fired two torpedoes from its stern tubes and the Lord Strathcona too went down within minutes.

The water was now teeming with injured sailors. The night was filled with their cries. Shore guns attempted to come to bear. Ships scrambled to get out of the bay. Small fishing boats raced to rescue survivors. In the confusion, U-513 slipped out into the Atlantic. Twenty-nine men died in the attacks.

The Bell Island Wrecks Today

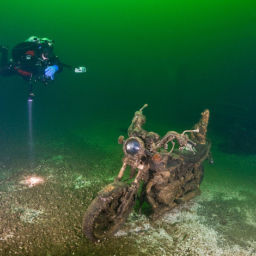

As I descend toward the superstructure of the SS Lord Strathcona, initially I see little evidence of that violent night. Covered with an abundance of sea life, it looks quite serene. But as I near the ship’s stern, I start to notice signs of the attack —metal parts twisted out of shape by the force of the explosions, an ugly hole gaping in the side of the ship. At the stern is the deck gun, locked into place and unused in the attack, now covered in a thick blanket of sea anemones. No longer threatening, the weapon now looks like a stuffed toy. The depth, between 90 and 120 feet (27 to 37 m), allows one quick circuit of the back half of the wreck — these ships were over 400 feet (122 m) long — and then it’s back to the surface.

A generous surface interval gives us an afternoon dive on the Lord Strathcona. This time we enter the superstructure to look for an old Marconi radio set still attached to one wall. We find it and still have time for look at the bow of the ship. On the way back to the ascent line, I meet two odd local residents — a lumpfish (stunning colors but looking like it met with a disfiguring childhood accident), and an ocean pout (I’m immediately reminded of Steve Tyler or Mick Jagger). In this cold water, at these depths, two dives are the limit for the day.

The PLM-27

On our second day, we explore the wreck of PLM-27, a Free French Naval Forces ship torpedoed during the second round of U-boat attacks.

It was November 2, 1942. Hugging the cliffs, U-518 slipped quietly into the bay. This time the captain, Friedrich Wissmann, decided on a night attack. His first shot missed its target but hit the pier on Bell Island, causing substantial damage.

U-518 swung around and lined up a second shot on the SS Rose Castle. Two torpedoes found their marks, one in the stern and one in the bow. The Rose Castle went down. Of the 43 crew, 28 men lost their lives.

U-518 continued its attack. The PLM-27 (Paris, Lyon, Marseilles) was moored near the Rose Castle. It had fired flares to help survivors from the torpedoed ship, and U-518 used the lights to line up a perfect shot. PLM-27 took a torpedo dead amidships. It split almost perfectly in two and 12 men were killed. Once again, in the confusion the U-boat slipped out of the bay and back into the Atlantic.

PLM-27 is the shallowest of the four wrecks, with the main deck at only 60 feet (18 m). So although the cold is still biting at me, as I make my way around I’m able to take a little more time exploring. I start deep at the massive propeller and rudder. One prop blade is missing a massive chunk. Apparently the ship went down so quickly that the spinning propeller hit the bedrock, shearing the metal. I make my way along the side until I come across a 30-foot (9 m) gap in the hull. It takes a few seconds to register what I’m floating in: a torpedo hole. It’s sobering to imagine the force that punched this enormous hole in the side of a ship and peeled back 2-inch steel as if it was so much cardboard.

The SS Rose Castle

On our third day we go deep on the SS Rose Castle, a delight for the tech divers. The deck starts at 110 feet (33.5 m) and by the time you get to the keel you’re pushing past 160 feet (48 m). The depth has ensured that the wreck has stayed intact. The cranes look as if they could be put to use if you just scraped off the anemones and used a little grease.

The SS Saganaga

Our final day of diving the Bell Island wrecks puts us on the SS Saganaga. This wreck’s a little less daunting in terms of depth with the superstructure sitting at around 60 feet (18 m) and the main deck around 80 feet (24 m). Again I’m impressed by how much debris of war remains scattered around the deck: a 2-ton anchor blown from the bow 200 feet (61 m) away, 5-inch shells scattered about, and boxes of bullets littering the deck. I’m tempted to take a bullet as a souvenir, but then I remember that this is a war grave. I retract my hand and continue to explore —30 minutes later, another magical dive is over way too quickly.

Four days and eight dives later, I conclude that the Bell Island wrecks are among the best cold-water dives I’ve ever experienced. Despite the intense cold, I’ll be back next year and for many years to come.