Almost everyone has a favorite movie that they can watch repeatedly without tiring of it, and the story often becomes more enjoyable on the 2 or 3 viewing, as the plot becomes familiar and the characters become like old friends. Scuba diving is no different — we are often drawn to a particular dive destination over and over, and like a good movie our favorite sites consistently entertain and inspire us without becoming boring.

One of my favorite repeat dive destinations is the Galapagos Islands. Within this archipelago, the dive sites at Darwin’s Arch and Wolf Island are approximately 24 hours by boat, across an open sea, from the southern islands, making them one of the world’s more remote dive sites. During my diving career I’ve come to suspect that the better the dive site or destination, the harder it is to get there, and the Galapagos Islands, particularly the dive sites of Darwin and Wolf, reinforce my theory.

Source Wikimedia Commons

So if these islands are so remote and difficult to travel to, what draws me back, time after time? Schools of hundreds of hammerheads, Galapagos sharks, reef sharks, whale sharks — with many sightings of pregnant females — turtles, sea lions, mantas and eagle rays, eels and hundreds of schooling fish of different species — the marine life is simply astonishing. I’ve seen orcas hunting and passed a humpback and her calf on the way to a dive site. The aquatic life and the behavior that you’ll witness truly make these islands a diver’s Mecca and worthy of at least one trip in your lifetime — it’s a true bucket-list dive destination.

Despite the remoteness of these northern islands of the Galapagos, I am willing to lug around not only my standard dive equipment, but also, on my last three trips, a closed-circuit rebreather, with a fourth rebreather trip planned for September 2015. And if you think hauling standard dive gear is an inconvenience, traveling with a closed-circuit rebreather multiplies the headache and worry by a factor of 10. Galapagos travel nowadays is easier for rebreather divers than in years past thanks to the local logistical support, tank rental and sofnolime supply from Galapagos resident and rebreather guide and instructor Jorge Mahauad of Galapagos Rebreathers/Tip Top Diving.

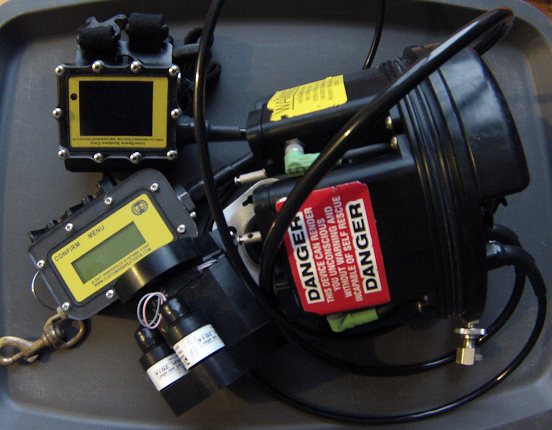

In addition to the issues most scuba divers face with baggage allowances and carefully packing gear, rebreather divers tend to have even heavier equipment and must take even more care and security in their packing, as it is unlikely a dive resort or live-aboard operator will have spares should any damage occur in transit. Because of this, many rebreather divers choose to take some of their parts, particularly the “electronic head” as carry on. Unfortunately, most electronic heads resemble explosive devices — at least to the TSA agents who regard me with frigid stares each time the electronic head is passed through the security checks. Travel inevitably requires breakdown of all carry-on baggage and a short seminar on rebreathers, and ends with me convincing the agents that it is safe, with the enthusiasm of a door-to-door salesman.

Don’t say what it looks like near TSA. Photo courtesy – Andy Phillips

By now you may be wondering if I’m trying to convince or dissuade you from diving the Galapagos on a rebreather. In spite of the travel and transportation issues, this is the only way I would ever dive the Galapagos, and simply put, the rewards far outweigh the hassles. Using a closed-circuit rebreather means extended no-decompression limits, more intimate encounters with the aquatic life, better photographs and video and warmer physiology and hydration. Rebreather divers get extended time in the water, so rather than trying to fit in four or five dives of 60 minutes each per day, gearing up multiple times (think of putting on a cold, damp 5 mm wetsuit 4 or 5 times day), and traveling between the live aboard and the sites on the pangas, rebreathers allow dives of two to three hours twice a day, which makes them much more efficient.

This extended bottom time generally means that divers will blend in more with the environment; it was common for us to start getting our best action of each dive once we’d been underwater an hour — and by best action I mean having whale sharks sneak up behind us. This intimacy with the aquatic life, and my ability to video or photograph it, is my primary motivation for using a rebreather.

While diving my rebreather on previous Galapagos trips, I developed a hypothesis that the schools of hammerheads can actually sense the electronics and solenoid in the head of the rebreather, and this draws them nearer to the diver — cynics please wait, video footage coming soon— making for an even more enjoyable encounter.

But don’t take just my words for it — I’ll wrap up this article with two of my short video clips, both filmed on a closed-circuit rebreather in the Galapagos.

This clip was filmed in August 2011 on my rebreather, and shows how the hammerheads pass over me, very curious, and circle to come back for a second look. This was the moment I felt they could sense the electronics inside my unit.

This clip was filmed in September 2013 and there were probably 12 of us on rebreathers in the vicinity, filming a school of hammerheads. As we were filming the school, one of the divers noticed a whale shark on the other side of the school swimming towards us and through the hammerheads, hence why we are screaming and laughing like school kids.

On our latest trip, the rebreather divers compared diving on open-circuit scuba and rebreather to watching a movie in 3D compared to 2D. The Galapagos will always deliver amazing sightings of aquatic life, but when you travel that far, to some of the best dive sites in the world, do you want to watch from the sideline or be in the game? Now that’s reason to haul myself, and all my gear, back for our next rebreather trip in September 2015. Who’s joining us?