Between May and July each year, there’s a giant cuttlefish aggregation in Whyalla, Australia. The world’s largest species of cuttlefish congregate by the thousands to breed in the shallow waters between Fitzgerald Bay and False Bay in Whyalla in South Australia’s Spencer Gulf. It’s one big cephalopod orgy and it’s a spectacular sight.

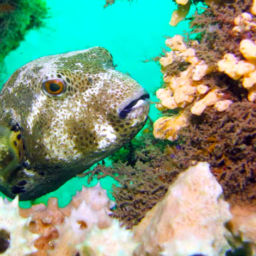

Cuttlefish (Sepia apama) are actually not fish at all, they are cephalopods. Their name, translated literally, means “head foot” — which kind-of makes sense when you look at them. Their feet (eight tentacles) are directly connected to their head. They use their tentacles, which are a bit like over-developed lips, for grabbing, moving and camouflage. The two feeding tentacles are smooth but tipped with a testicular club covered with suckers. They use these to catch their prey, which they then secure and eat with their beak-like mouth and a tooth-lined tongue.

For their annual breeding aggregation, the cuttlefish must be as large and strong as possible, so energy efficiency is a major part of development in preparation for this event. Once into the mating season, the cuttlefish expends all of its energy, fertilizing as many females as possible. From late May onwards, hundreds of thousands will congregate with nothing but sex on their minds. They’ll mate and lay eggs until late August or early September; after this marathon of three to four months of endless sex, most die from the sheer exhaustion.

Witnessing the cuttlefish aggregation in Whyalla

Witnessing this incredible event for the first time — any time really — is incredibly exciting, and the weather on our first day of diving allowed for a great display. The seas were flat calm and the sun was shining. June in South Australia can be cold and windy but we were lucky. I was ready to become a voyeur for the day.

Watching the cuttlefish from the surface encouraged me to jump in quickly — there were so many. The males arrived before the females, indicating that the area attracted males and not congregating females. Males outnumbered the females by as many as 11 to 1, so you can imagine the intensity of competition. With that many suitors, the females can refuse up to 70 percent of advances and still consummate with multiple males. The courtship ritual consists of vibrant displays of pulsating patterns and fluorescent shades of colors. The more the male can impress her, the better his chance of mating with the female.

Watching the displays

Cuttlefish are very intelligent and indicate that they’re ready to mate with a swift change of color. Their skin seemingly electrically charged, they put on brilliant displays using special embedded chromatophore cells. Their skin glitters in a kaleidoscope of colors with each male cuttlefish trying to out-flash the other for the female’s attention. As they fight for attention larger males show their superior size, while the younger, less-experienced males don’t stand much chance.

But the game’s not up for the small males — they become what we call “sneakers,” as they have developed a sneaky way to sidestep their competition. Being such clever creatures, the smaller male cuttlefish disguise themselves as females, changing their coloration and pulling in their longer tentacles to form a female shape. When the large males are distracted, they slip in undetected and quickly mate with the female. The shrewdness of this cross-dressing tactic seems to work, as the females value the cunning mating skills of these small males. The “sneakers” purportedly have a 60 percent success rate.

When the mating takes place, it is in the head-to-head position with some males being extremely rough, dragging the poor female around. Other males have a gentler approach — they stay and protect the female while she deposits her eggs. The larger male cuttlefish that did not reach sexual maturity in time for the previous year’s mating season can reach almost 5 feet (1.5 m) in length and vigilantly defend the smaller females.

With literally hundreds of cuttlefish surrounding you, it is hard to watch the multiple mating sessions happening. Shallow depths of about 10 to 16 feet (3 to 5 m) mean you can spend hours there — and that still leaves you wanting more.

It’s no surprise that snorkelers and divers from around the world converge here to observe this unique reproductive event. The giant cuttlefish aggregation in Whyalla is a must-see to believe.

Dive conditions

Depth: From 10 to 16 feet (3 to 5 m)

Visibility: Generally very clear at around 33 feet (10-plus m), however you can see cuttlefish clearly in vis as low as 13 feet (4 m).

Water temperature: 54 to 59 F (12 to 15 degrees C)

Recommended exposure protection: You’ll likely want at least a 7mm wetsuit or even a drysuit if you feel the cold particularly keenly

Water conditions: There are several points of entry along the 3.7 miles (6 km) of coastline in False Bay. However, the easiest points of entry are at Stony Point and Black Point, where there is a concrete apron and stairway to the beach. It is possible to drift dive between these two locations. Inside False Bay there is little to no current; at Point Lowly, however, there can be strong currents.