The documentary acted as an exposé of the conditions that affect captive orcas, focusing particularly on the practices of SeaWorld facilities around the United States. The film was inspired by the death of SeaWorld trainer Dawn Brancheau, who was killed in 2010 by a captive bull orca SeaWorld in Orlando, Florida. The furor caused by Blackfish resulted in heated rebuttals from SeaWorld and a rising tide of public outcry against keeping orcas in captivity. On March 7th, this outcry resulted in the proposed Orca Welfare and Safety Act in California. According to Animal Welfare Institute marine mammal scientist Dr. Naomi Rose, the bill constitutes the first “serious legislative proposal to prohibit the captive display of this highly intelligent and social species.” Proposed by State Assemblyman Richard Bloom, the act would make it illegal to “hold in captivity, or use, a wild-caught or captive-bred orca for performance or entertainment purposes” within the state of California.

If passed, this legislation would constitute a significant landmark in the fight to end orca captivity; perhaps even creating a precedent for the closure of cetacean entertainment shows nationwide. The influence of Blackfish is clear, not only because Assemblyman Bloom contacted the documentary’s director Gabriela Cowperthwaite for assistance with putting the bill together, but also because it shares a common target with the film. As the only California facility with captive orcas, SeaWorld San Diego would be the only party to suffer if this legislation passes. The Orca Welfare and Safety Act would not only prohibit the captivity of any orca, but would also ban the artificial insemination of orcas in California as well as import of orcas or their semen from outside state borders. In this way, the act would effectively circumvent all possible methods of obtaining new orcas for SeaWorld’s existing displays.

According to the proposed law’s terms, violators would face fines of up to $100,000, and/or six months imprisonment. The whales already held in captivity by SeaWorld San Diego would be subject to rehabilitation programs and an eventual return to the wild when possible. A lifetime in captivity would presumably make this goal unrealistic for the majority of the whales, in which case they would be transferred to sea pens and no longer used for entertainment or performance purposes. Exemptions would exist in the case of stranded orcas, necessitating temporary capture for rehabilitation, and for orcas held for research purposes. Ultimately, all orcas held in captivity for any reason would have to be returned to the ocean or a sea pen eventually by law.

Assemblyman Bloom argued the case for his proposal in a written statement that said, in part “there is no justification for the continued captive display of orcas for entertainment purposes. These beautiful creatures are much too large and far too intelligent to be confined in small, concrete pens for their entire lives. It is time to end the practice of keeping orcas captive for human amusement.” SeaWorld predictably greeted the proposed legislation with anger, and their spokesman David Koontz criticized it as aligning with extreme animal rights activists’ “out-of-the-mainstream thinking.” He maintained that SeaWorld is “one of the world’s most respected zoological institutions” and that its practices are “already governed by multiple federal, state and local animal welfare laws.” SeaWorld Entertainment owns three facilities within the U.S., one each in California, Texas and Florida. The main attraction of each of these facilities are their captive orcas- SeaWorld owns 23 whales, with 10 of those falling under the jurisdiction of the proposed Orca Welfare and Safety Act. The entertainment corporation is the single biggest owner of captive orcas in the world, explaining why it has become the lightning rod for debates about the morality of keeping the whales in captivity.

Blackfish argued that captive orcas are prone to aggressive tendencies, both towards each other and the humans who come in contact with them. Dawn Brancheau’s death in 2010 was not an isolated event; orca Tilikum has been implicated in two other deaths. Bloom’s proposal begins with a reference to Brancheau’s death, pointing to the incident as tragic proof of the inadvisability of keeping intelligent orcas in captivity. Boredom, the trauma caused by the intentional separation of family members, the insufficient size of holding tanks, the bullying of young or new whales by other orcas and the questionable practices involved in training and breeding captive orcas are all thought to contribute to the apparently increased aggression of animals like Tilikum. Blackfish touched on all these issues, and was summarily dismissed by SeaWorld as being inaccurate. Shortly after the film’s release, SeaWorld issued a statement referring to the “millions of dollars committed annually [by SeaWorld] to conservation and scientific research.” It is certainly true that the ethicality of orca captivity has many gray areas — some argue that the education and research value of captive whales, and accessibility to the public justify the negative impacts on a relatively small number of individuals. And 80 percent of the whales owned by SeaWorld were born in captivity, and thusly have never experienced life in the wild.

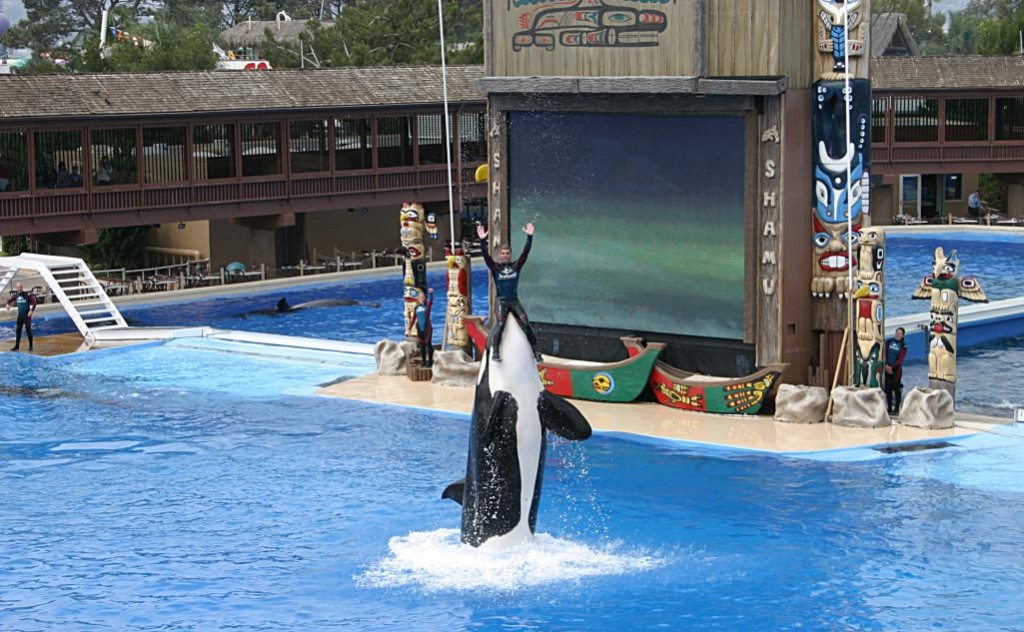

The fact remains, however, that orcas — or any intelligent cetaceans — are not meant for captivity. These wild animals are not supposed to spend their lives jumping through hoops — literally — for human entertainment; neither should they be forced to reproduce far more frequently than they would in the wild to meet the demands of lucrative inter-facility purchases. Often whales are separated from their immediate family members during these trades. For animals that display some of the most evolved social bonds in the animal kingdom, this practice cannot be deemed humane. In the wild, the average lifespan for a male orca is 30 years, and for a female, 50, with a maximum lifespan of between 60 to 90 years depending on their gender. Most captive orcas die before they reach 20, with only a few individuals surviving beyond 35 years of age. Orcas in captivity suffer an annual mortality rate 2.5 times higher than wild whales, providing further evidence of damage that imprisonment causes to a whale’s physiology. The mental repercussions of life in captivity we can only guess at, though facilities like SeaWorld take little note of these — Tilikum is currently performing once more in Florida.

In light of what we know about cetacean intelligence and the potential dangers to both the whales and their human keepers, it is difficult to justify keeping orcas in captivity. While aquariums do have educational value, as well as the power to raise marine conservation awareness, they can achieve these goals without cetacean shows. The only real value of whales and dolphins in captivity is monetary — they bring in millions in revenue each year for the facilities that own them.

As public opinion moves in favor of the whales, perhaps it is time for businesses like SeaWorld to abandon corporate greed, and instead join the effort to end the cruelty rather than fight it. The legislation proposed by Assemblyman Bloom on March 7th is not the first of its kind; it follows in the footsteps of South Carolina’s decision to prohibit dolphin captivity in 1992 and New York’s decision to ban orca captivity last month. Several countries around the world have already banned cetacean captivity completely, including India, Croatia, Hungary, Chile and Costa Rica. While it may not be the first law of its kind, if the Orca Welfare and Safety Act passes, it may well be the most important. Banning orca shows in even one of SeaWorld’s facilities may just trigger the landslide needed to bring an end to cetacean captivity in the U.S., if not worldwide.