Decades before the famous Panama Canal was constructed, the journey through the Panamanian jungle to another ship was the most efficient way for ambitious gold-seekers to travel from the East Coast of the United States to the West. With the onset of the California Gold Rush, steamships were in constant competition to reach higher speeds and lure more passengers. That competition ultimately led to the demise of the SS Winfield Scott. It’s now a popular dive site within Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary.

The California Gold Rush

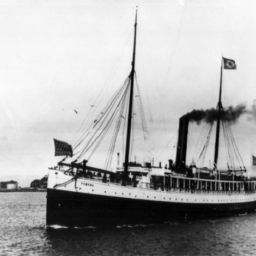

Named in honor of the “Grand Old Man of the Army,” General Winfield Scott, the SS Winfield Scott was built in 1850 in New York. The vessel began its life on the Eastern Seaboard, spending two years sailing between New York and New Orleans. In 1852, it departed New York for San Francisco to begin service on the Panama route.

The California Gold Rush was in full swing, with thousands of people seeking their fortunes. As prospectors waited on the west coast of Panama for a ship to take them to California, Winfield Scott arrived just in time to join the steamship competition of which ship could get explorers to the California goldfields the fastest.

With this transportation boom, the promise of gold not only populated the state of California with miners, prospectors, and merchants, but also populated the California and Mexico coastlines with a number of shipwrecks. Most ships stayed clear of the Channel Islands as they are challenging to navigate. Excessive speed, directional miscalculation, and weather all caused wrecks in this area. However, past misfortune has become our time machine, as the shipwrecks in Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary have left us with an underwater footprint of our nation’s history dating back centuries , even to Native American maritime excursions.

The wreck of the SS Winfield Scott

On a cold, fateful December day in 1853, Winfield Scott carried gold, mail, and more than 450 passengers and crew leaving San Francisco bound for Panama. It was a foggy evening, making navigation difficult. Despite the challenge, the desire for speed won out and Captain Simon F. Blunt decided to take a popular shortcut through the Santa Barbara Channel. In his confidence, he blazed ahead, paddlewheels turning, and steered directly into Middle Anacapa Island.

Water rushed in and the passengers were ordered off the ship. Crew ferried them in lifeboats to a small rock, where they spent the night. Crew later transported the passengers to Anacapa Island, where they camped for eight days until the side-wheel steamship California rescued them. The crew spent that week and more attempting to recover what they could from the shipwreck. A journal of one of the passengers, Asa Cyrus Call, is still retained by his family as a testament and first-person account to this piece of history.

Diving the Winfield Scott

In the decades after the wreck, teams salvaged the SS Winfield Scott using dynamite. The wooden hull has disintegrated with the motion of the sea and has succumbed to wood-boring organisms. Still, the machinery that was not salvaged in the 19th century remains intact and marine life now carpets the wreckage.

While swimming through the shipwreck of Winfield Scott, it’s easy to imagine the California Gold Rush history that brought so many seafarers through this area. The dive provides insights to the massive steam-powered machinery that once propelled the ship, fully loaded, at 11 knots. Key artifacts include one of the steamer’s paddlewheel shafts with flanges, paddlewheel shaft support, paddlewheel bracing, and the base of one of the piston cylinders. These artifacts are now at home among the kelp forest and sea life. Resting in 25 to 30 feet (8 to 9 m) of water, Winfield Scott offers both divers and snorkelers a glimpse of Gold Rush history.