Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary is a treasure trove of natural and culturally unique resources. Today, the sanctuary covers 1,470 square miles, and surrounds five of the Channel Islands off the California coast. Maritime heritage in the sanctuary dates back to when Native Americans used plank canoes, known as tomols, to trade and fish. Shipwrecks within the sanctuary tell the story of hundreds of years of travel on the seas.

The history of the SS Cuba

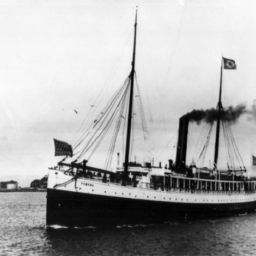

One shipwreck within the sanctuary is the SS Cuba. This vessel’s remains rest on the ocean floor off of Point Bennet, on the west end of San Miguel Island. Divers can check out the Cuba’s late-19th-century steam power machinery. The triple-expansion steam engines and boilers are still in their original upright position, 94 years after the vessel stranded.

The Blohm and Voss Shipyard built the Cuba, then called the Coblenz, in 1897 in Hamburg, Germany. The shipyard famously produced the German battleship Bismarck and the sailing vessel Horst Wessel, now known as the U.S. Coast Guard training ship Eagle. Americans took control of the Coblenz when it was confiscated at a Philippine port upon the United States’ entry to World War I. The Pacific Mail Steamship Company bought the ship from the United States Shipping Board in 1920 and renamed it Sachem, and later, Cuba. The Cuba continued service as a passenger-cargo ship between San Francisco and Cuba via the Panama Canal Zone.

In September 1923, Cuba passed through the Panama Canal Zone on the way to San Francisco with 41 passengers and 71 crewmen. After reaching Mexico on September 3, the ship worked its way up the coast, encountering thick fog. The crew had to navigate by dead reckoning — navigating by course, speed, and time elapsed without a fix on land. When the radio stopped working, crew could not muster any spare parts to fix it.

On September 7th, four days into the journey through the thick fog, Captain Charles J. Holland, master of Cuba, placed Second Officer John Rochau in command so that he could rest. He was to be roused if visibility dropped below five or six miles, and no later than 3 a.m. in order to take soundings. First Officer Wise woke the captain at 4 a.m., and Holland found visibility had fallen to less than four miles.

As Captain Holland took charge and attempted to turn the ship to port, the ship struck a reef about a quarter-mile off of San Miguel Island. Realizing what had happened, he ordered the engines reversed. Cuba was able to briefly escape the reef, only to have waves toss it back into the reef it had struck moments before. This destroyed the twin propellers, disabling the boat.

Realizing that the ship was sinking, Captain Holland ordered the passengers and most of the crew into lifeboats. He, the purser, the steward, and eight crew members stayed aboard to protect Cuba’s cargo, which included silver bullion, mahogany, and coffee. All the crew and passengers survived and most of the extremely valuable cargo was saved. The ship, however, sank near San Miguel Island.

Diving the SS Cuba

Today, Cuba is a popular sanctuary dive site. The shipwreck is unique in that it is one of the most consolidated and organized of over 150 historic wrecks in Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary and Channel Islands National Park. Divers can still see the deck equipment in place despite the wreck’s location in a region that is commonly impacted by ocean swells.

By guest author Emma Skelley, NOAA Office of National Marine Sanctuaries