Traveling to abroad often means we’ll have to contend with the potential risks from untreated tap water, mosquito bites or excessive sun exposure, among other things. But divers face risks underwater as well. Different diving environments often present unique hazards, specifically with regards to marine life. Here we’ll address five common tropical marine life injuries — how to avoid them in the first place, and how to treat them if you’re afflicted. Disclaimer: Keep in mind that this article is not intended to replace professional medical treatment. If you are seriously injured, seek medical care.

Jellyfish

Jellyfish

There are hundreds of types of jellyfish, and a sting is one of the most common tropical marine life injuries. Reactions vary from person to person, but can include none at all, numbness, a mild itch, or severe pain. You can even die from some particularly potent stings. The sting occurs when skin comes into contact with jellyfish tentacles that have microscopic barbs, which release toxins into the skin. Divers should beware of floating, transparent shapes in the water.

Even broken-off tentacles washed up on a shoreline can release toxins if stepped on. Wearing a full-length wetsuit or rash guard helps protect vulnerable areas. If stung, do not rub the wound, as this will intensify and possibly spread the affected area. Instead, irrigate the area with household vinegar. Remove any tentacles with tweezers and gloves, and rinse with salt water. A hot pack of around 113 F (45 C) can help reduce pain as well. Physicians may recommend painkillers, anti-inflammatory meds and topical anesthetics.

Coral scrapes

Coral scrapes

Coral scrapes are also very common tropical marine life injuries, but you can easily avoid them by staying aware of your surroundings. Excellent buoyancy control is also key here. A full wetsuit or dive skin can protect your skin, but do not use it to compensate for poor buoyancy skills. Macro photographers are particularly at risk when they get close to the reef and corals to photograph subjects. Watch for signs such as redness, swelling, inflammation and tenderness.

Symptoms will vary depending on the scrape’s severity, but can include pain, burning and itching. If coral scrapes you, clean the area immediately with soap and water. This will prevent further inflammation and infection, which is a common side effect of a coral scrape. If you’ve touched a fire coral, try hot water or a hot pack, again around 113 F (45 C). If irritation persists, a physician will typically prescribe an anti-inflammatory or an antihistamine.

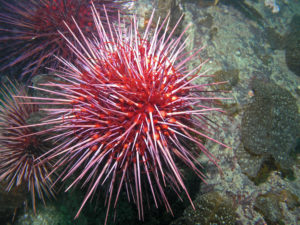

Sea urchins

Sea urchins

In addition to causing puncture wounds, sea urchin spines are often venomous. If a diver or snorkeler stands on or touches an urchin, they may feel immediate pain, burning, swelling and numbness. If not treated properly, infection is also a further risk. Avoid touching urchins — avoid touching anything on the reef — or getting close to them while diving. Wear booties when shore diving and take special care when moving through surf zones near rocks. If you are stung by an urchin, elevate the injury, remove spines with tweezers, irrigate the area and clean with antiseptic lotion. Break down the spines remaining in the body by soaking the wound in hot water with Epsom salts on a daily basis. For more complicated infections, apply a pressure dressing to prevent venom spread and seek medical care.

Stingrays

Stingrays

Stingray injuries are thankfully quite rare for scuba divers. Swimmers and snorkelers walking in shallow water at the shoreline are at a much higher risk, and injuries usually occur on the feet and lower legs when the accidentally step on a stingray. Although individual reactions vary, if stung the pain can be intense. Victims may require treatment for shock. Irrigate the wound in salt water to remove any stingray spines and remove any foreign bodies with tweezers. Apply a dressing to stop bleeding and soak in hot water for up to 90 minutes. Then, clean the wound with soap and water. More severe cases will require a doctor visit, as stings can be fatal if taken in the torso region.

Lionfish

Lionfish

Just as the other hazardous marine life injuries we’ve addressed, lionfish stings are best prevented in the first place. Practice good buoyancy control and keep a respectful distance from lionfish. In recent years, Caribbean divers have reported the most injuries from stings while spearing the invasive lionfish, which is not native to the region. Any divers engaging in spearing or containment activities in the Caribbean should get proper training and, in some regions, licenses.

If your skin is punctured by any of the animal’s 18 venomous spines, you’ll usually feel immediate, intense localized pain and throbbing. The most important thing during this situation is to calm your breathing and response, slow your ascent rate and ascend safely to the shoreline or boat. First aid involves removing the spines with tweezers. Even broken-off spines can contain venom, so take care with removal and disposal. Clean the wound with fresh water and disinfectant, and apply antibiotic cream if possible. If the wound is bleeding, apply a direct-pressure bandage to control blood flow. To alleviate the pain and break down the venom and toxins, soak the injured area (or apply soaked pads) in hot water around 113 F (45 C) for about 30 minutes. Many dive operators that engage in lionfish containment activities will have commercial hot packs on site.

Prevention is always better than cure when it comes to common marine life injuries, so avoid getting too close to aquatic life. Maintain good situational and environmental awareness, practice excellent buoyancy control, and never, ever touch anything underwater. But because stings and spines stuck in the skin can lead to infection or tissue necrosis, victims should always seek professional medical assistance after conducting first-aid treatment.