The Mount Everest of Scuba Diving

The desire to achieve something – or what we often refer to as motivation – can come from many different and varied influences. Perhaps watching a role model or friend perform well in a particular sport makes us strive to excel, or maybe a National Geographic/Discovery Channel show piques our curiosity to travel to a particular destination. It could be the achievements of others in their personal and professional lives, too, that make us raise the bar and standards in our own games. In my own diving career, it was a combination of these types of influencers – reading the book “Shadow Divers” about John Chatterton and Richie Kohler, seeing footage on the Doria and aspiring to advance as a technical diver – that recently motivated me to dive the Andrea Doria. And while the initial seeds were sown in my mind almost 10 years ago, it wasn’t until this year that the opportunity finally presented itself.

Diving the Andrea Doria

One of the first questions many of my friends, colleagues and other divers I know asked me after the trip was, “How was it?” So I wanted to share my experience in a brief trip report. Maybe this will serve as an influencer or motivator for others to make the transition into technical diving or to simply advance their own diving and extend their limits, even if still at the outer edges of recreational diving.

Now, if you’re unfamiliar with the type of dive site and the history of the shipwreck of the Andrea Doria, you could be forgiven for thinking that I’m a slow mover in having waited 10 years to make this dream a reality. Many technical divers familiar with the wreck consider the Andrea Doria to be the Mount Everest of scuba diving. And it’s not just the wreck’s depth range (around 200-250 feet/60-75 meters) that makes this a challenging dive beyond the limits of recreational divers – it’s the location, too. The Andrea Doria is in Nantucket, Massachusetts, in the northeast United States, an area with extremely strong currents that makes hand-over-hand descents and ascents mandatory, as well as the use of jon lines (many divers even choose to use scooters for efficiency and to save energy). The cold, dark waters of the northeast Atlantic also add to the challenge, with bottom temperatures between 40 to 48 degrees Fahrenheit/4 to 7 degrees Celsius and visibility, on a good day, hovering around 25 feet/7 meters.

Traditionally, I would consider myself a warm-water diver when it comes to both recreational and technical diving. The island of Utila, where I teach and train dive professionals and technical divers, has average water temperatures of between 84 to 88 degrees Fahrenheit/26 to 28 degrees Celsius year round and visibility between 60 to 100 feet/18 to 30 meters. Utila also has very weak to mild currents, and while they make for a perfect training environment to learn the motor skills for tec diving and transition from recreational to technical diving, I was nonetheless required to undertake a period of training to prepare myself for the challenges of the Andrea Doria. Even though I already had prior dive experience in cold water and had also experienced strong currents at depth with low visibility, never had I experienced all of these variables at the same time. And that combination could be akin to the ‘perfect storm’ for a tec dive on the infamous shipwreck that has claimed the lives of many a tec diver far more experienced than I am.

The trip I had booked was scheduled for a departure date out of Long Island, New York on July 5, 2013, with two dives scheduled for each day on the Saturday and Sunday before leaving the wreck for the 16-hour return boat ride to New York. As I mentioned earlier, an opportunity to be part of a trip like this can take time to present itself. But when I first heard about the dates and was invited by a friend, I knew that I would be spending two months in Quebec, Canada prior to the trip – it presented the perfect opportunity and diving environment for me to train in conditions similar to the Andrea Doria’s. My goal was to advance my own comfort, skill level and awareness (see the link at the end of this article to read more about the lessons I learned during this transition).

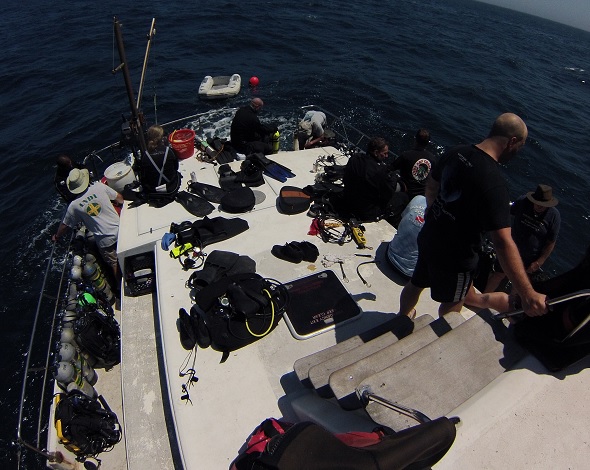

My dive partner, Dave, from Pennsylvania, picked me up from La Guardia airport and we drove two hours up to Captree Park in Long Island where we loaded 16 tanks onto the boat for our weekend of diving. There were eight other passengers doing the same – all open circuit tec trimix divers, two closed-circuit trimix rebreather divers, and four members of the crew and the famous Captain Hank of the boat the Garloo (formerly known as the Wahoo). With a rich history, the boat is one of the original northeast wreck charter boats and was frequently mentioned in one of my reading resources, “Setting the Hook: A Diver’s Return to the Andrea Doria,” by Peter Hunt. It was a privilege to step foot on the vessel.

We departed the harbor around 3.30pm and had nice calm conditions for the 18-hour ride. I was grateful at this stage that I was so used to working on boats as many of the other passengers suffered from seasickness. Although the living quarters were cramped and space was at a premium, the crew excelled in preparing a great meal, after which most people went to bed early in order to be rested for the dive of a lifetime.

We arrived at the site of the Andrea Doria around 9am. It took close to an hour for the crew to set the hook, which involved quite a bit of manoeuvring by the captain to get the boat in place. Then the weights/hook, with a folded lift bag attached, were dropped over the side attached to a buoy as one of the crew descended down the buoy line to secure the hook to the Doria. He shot a marker up once this was secure. The captain then took the boat and secured it to the buoy and lines were attached to each side of the boat leading to the buoy/descent line, which would be critical for both entering the water and descending/ascending. After the two crew members had surfaced, they briefed us on a very strong current with visibility around 25 feet/7 meters and a bottom temperature of 48 degrees Fahrenheit/7 degrees Celsius. By Doria standards, the conditions were great!

So here we go, no drills – this was the real deal. After months of preparation and training, the excitement was bubbling inside of me as Dave and I began to gear up. Although the waters of the northeast Atlantic are frigidly cold, the topside conditions were anything but. It was a bright day and very sunny as we geared up into drysuits and doubles – a strenuous process that required assistance from the crew as we had to fully kit on the boat, including the stage tanks. Dave entered the water first and then I followed with a giant stride and grabbed hold of the grappling rope alongside the portside, catching my breath from the chill of the water. We immediately dropped below the surface and used the lines to pull ourselves against the current with a slight incline as we approached the bow mooring. Then we descended down the anchor line. This was no swimming descent but rather a hand-over-hand pull down the line through plankton-green waters. We were probably inclined about 45 degrees and resembled flags on poles on a very windy day. My dry gloves strained against their seals and I could feel cold water seeping into the dry suit as I braced myself for the accompanying chill. All in all, the descent was probably over a line that had been laid out 600 to 800 feet. Due to the length and current, it took us 12 minutes to get down and I had even blown off 800 psi – almost the equivalent of 1600 psi from a single tank. That’s approximately $30 of helium from my valuable bottom mix of 17% O2 and 49% helium, leaving 34% nitrogen and an equivalent air depth at 220 feet/66 meters of less than 100 feet/30 meters.

As I approached the bottom through the green waters, the shadow of the Andrea Doria loomed into view and I wanted to yell out in excitement. But I kept my cool and focused on what was around me. The current had weakened as we dropped below 150 feet/45 meters and the water had stopped leaking through the seal, and I knew the undergarm would soon transfer the water away from my body. We touched down at 220 feet/66 meters. There was part of the structure slightly higher than this, but it was probably deemed too unstable by the crew, who had chosen not to attach the hook there. I checked my gauges for gas supply and depth, noted the anchor line that would be, in no uncertain terms, my return point for the ascent. Free ascents in open water are not viable at the site of the Andrea Doria and the currents of the Nantucket straits.

So excited and in awe was I that I was actually on the Doria that I pulled a ‘slam dunk’ with my hand onto a part of the wreck next to me (gently so as not to perforate my dry glove) and called out a “#*&% yeah!” into my second stage! I was transfixed with the age of the metal and the growth on parts of the ship. To be honest, I could have been dropped onto any piece of scrap metal in the northeast Atlantic, as there was no way to comprehend the size of the Doria – especially with the limited visibility. The visibility was not only low but the waters were pitch black, and our lights cut through it as if we were on a night dive. I observed hazardous fishing line and nets that had caught on the wreck, and I was surprised by how much marine life there was to see. I had an internal feeling of contentment to be on a ship that had so much rich history, both as it crossed the waters between Europe and the New World and as the dive site which had claimed so many experienced divers while at the same time delivering so much accomplishment to other divers. Our first dive had been planned as an assessment/acclimation dive on the Doria, so we stayed close by the descent/ascent line until we hit our planned 20 minute time, and then made the ascent back to the boat. We made our ascent on the anchor line using jon lines for the current, making multiple decompressions stops/gas switches for a total run time of over 60 minutes. Upon surfacing it was critical to remain in contact with the line to get to the stern of the boat and exit in full gear up the ladder with stages and fins while the crew helped remove our tanks and gear. The gym training and leg presses that I’d been doing the last few months came in handy as I climbed the boat ladder in double steel 95cu ft. tanks and with a 40cu ft. and 80cu ft. slung on either side of me, slowly taking off my gear with a huge smile in place.

There were other teams still on decompression as well as ones that had already exited the water before us. And after we placed our undergarments and drysuits up to dry we rested and off-gassed the nitrogen/helium with an extended six-hour surface interval.

Aside from a slight chill in the arms and hands I had kept warm throughout most of the dive. Still, I welcomed the warm rays of sunshine on the deck of the boat as I changed over my tanks and prepared the equipment for the second dive later that afternoon before proceeding to sneak away for a siesta.

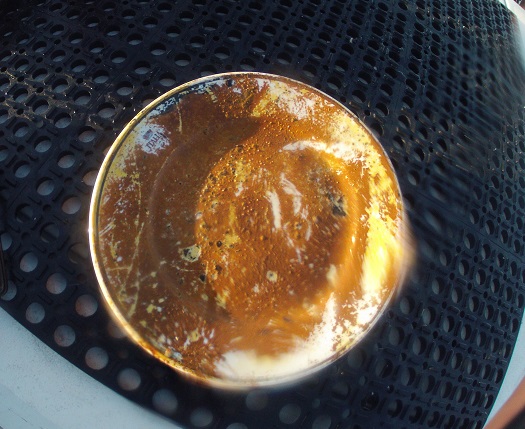

After approximately five hours on the surface we geared up for the second dive. We had a quicker descent this time as the current had dropped, but we still went hand-over-hand for the descent, making it to the bottom in about six minutes (half the time of the previous dive). Now that I had one Andrea Doria dive to my name I decided to carry the GoPro camera on this dive to get some footage, even if it was more for a souvenir as the conditions were not ideal for shooting. Some people later commented that the video I took looked more like a night dive than a day dive on a wreck. With more time actually on the bottom the second time around I got to explore more of the wreck, including some overhead sections. I was, however, always in a heightened state of alert knowing that navigation, gas-management and general awareness of entanglement were critical to not becoming another fatality. Ascending on the line, we passed a member of the crew who had been scootering and were on a longer decompression obligation. With a touch of envy, we could see a goodie bag of china collected from the Doria.

After surfacing and taking off my gear, I drank plenty of water and then, with the sun setting, toasted a few Yuengling beers to a successful day’s diving and my initiation on Doria.

We awoke early the next day since the plan was to depart that afternoon around 3pm. At 7am, there were a few divers on the deck gearing up. Disappointing news came from some of the crew, however – the current was more intense than on the first day and it was unlikely we would be able to dive right away. To reinforce his point, a crew member dropped a 30kg/70 pound weight overboard on a line and it was swept nearly horizontal by the current. Undeterred, one of the divers, Joe, an experienced northeast wreck diver from New York, decided he would give it a go anyway. The crew cautioned him to call the dive if he felt it was too strong, urging him not to be a hero. The remaining divers on deck waited anxiously as our newfound guinea pig prepared to splash down. Within seconds of hitting the water he was carried 20 feet/6 meters back to the stern where he managed to grab the grappling line in time, and then descended under pulling himself to the bow. Within minutes, Joe was back on the surface and we immediately knew that the day’s diving was called. Unless the current dropped significantly, we’d be going home with some tanks full of helium. After approximately four hours it looked like the current had dropped. But I was now close to the 24 hour window that I decided to leave for the no-fly off gassing. Although guidelines suggest only “beyond 12 hours,” this is based off recreational diving data and I wanted a more conservative window due to the nature of technical diving and the profiles we were conducting.

Of the ten passengers, only two decided to make the dive that day. Both were seasoned northeast wreck divers. Two crew members also decided to dive while the other two supervised, and the other eight passengers sat the dive out. In retrospect, it was probably the right call. The current was still strong and even resulted in a surface rescue when one of the divers exerted himself at the end of the dive and had a seizure while fighting the current to get back to the boat lines. Fortunately for this person, the crew and other passengers responded according to their training. And after the diver had been brought out of the water, the equipment had been removed and cut away and O2 had been administered, the person regained responsiveness. Now this may sound like a calm and controlled exercise, but in reality at the time it was not. We were hundreds of miles offshore in inhospitable conditions and had no idea what had happened to the diver, other than sensing he was minutes from cardiac arrest unless we had cut him from the dry suit and provided O2. Afterwards, Captain Hal’s words were: “It wouldn’t be a Doria dive without some type of excitement.”

So all in all, was it worth it? Yes, without a doubt – and not only for the site itself, but also for the training, preparation and adventure that went along with the whole Andrea Doria experience. As the old traveler’s adage goes, “Sometimes the journey is as good as the destination.” And I smiled on the return ride home at the fact that I had accomplished a pinnacle and summit in my own diving career, opening up a whole new realm of deeper, colder water diving on wrecks that heralded a new chapter in my diving adventures.

For anyone interested in the preparation and transition I undertook from warm water tec diving to cold water tec diving, here is an article on my blog: http://www.goproutila.com/tec-diving-warm-water-to-cold-water.