Our entry-level dive courses teach us about the causes and outcomes of diving accidents. Every good dive briefing should include information about how to avoid dangerous situations, and emergency procedures for coping with them should they arise. With sufficient training and preparation, we can easily avoid most diving accidents. Nonetheless, every diver should have at least a basic understanding of what to do if things go wrong. Although the danger potential may seem high, diving is actually a relatively safe sport when conducted sensibly. A roundup of data from the U.S., the U.K., Canada and Japan shows that the statistical chance of fatality while diving is 2-3 per 100,000 dives. The following list of rules is by no means exhaustive, but offers basic rules to minimize the likelihood of a dive accident.

Safe Scuba Diving

1. Never hold your breath

As every good entry-level dive student knows, this is the most important rule of scuba. And for good reason — breath holding underwater can result in serious injury and even death. In accordance with Boyle’s law, the air in a diver’s lungs expands during ascent and contracts during descent. As long as the diver breathes continuously, this is not a problem because excess air can escape. But when a diver holds his breath, the air can no longer escape as it expands, and eventually, the alveoli that make up the lung walls will rupture, causing serious damage to the organ.

Injury to the lungs due to over-pressurization is known as pulmonary barotrauma. In the most extreme cases, it can cause air bubbles to escape into the chest cavity and bloodstream. Once in the bloodstream, these air bubbles can lead to an arterial gas embolism, which is often fatal. Depth changes of just a few feet are enough to cause lung-over expansion injuries. This makes holding one’s breath dangerous at all times while diving, not only when ascending. Avoiding pulmonary barotrauma is easy; simply continue to breathe at all times.

2. Practice safe ascents

Almost as important as breathing continuously is making sure to ascend slowly and safely at all times. If divers exceed a safe ascent rate, the nitrogen absorbed into the bloodstream at depth does not have time to dissolve back into solution as the pressure decreases on the way to the surface. Bubbles will form in the bloodstream, leading to decompression sickness. To avoid this, simply maintain a rate of ascent no faster than 30 feet per minute. Those diving with a computer will be warned if they are ascending too fast, while a general rule of thumb for those without a computer is to ascend no faster than their smallest bubble.

Always remember to fully deflate your BCD before starting your ascent and never, ever use your inflator button to get to the surface. Use the acronym taught to new divers to explain a five-point ascent: Signal, Time, Elevate, Look, Ascend (STELA). Unless worsening surface conditions, diminished air supply or any other serious mitigating factors make it unsafe to do so, always perform your 3-minute safety stop at 15 feet, which provides a barrier of conservatism that significantly decreases your chances of decompression sickness. A recent paper on diving fatalities that combined research from the Diver’s Alert Network (DAN) in the U.S. and Australia and BSAC in the U.K. showed that an uncontrolled ascent was the precipitating factor in 26 percent of the fatalities analyzed.

3. Check your gear

Underwater, your survival depends upon your equipment. Don’t be lazy when it comes to checking your gear before a dive. Conduct your buddy-check thoroughly —if your or your buddy’s equipment malfunctions it could cause a life-threatening situation for you both. Make sure that you know how to use your gear. The majority of equipment-related accidents occur not because the equipment breaks but because of diver uncertainty as to how it works.

Make sure you know exactly how your integrated weights release and how to deploy your DSMB safely, and that you know where all the dump valves are on your BCD. If you are preparing for an unusual dive, make doubly sure that you’ve made all the appropriate equipment arrangements; for example, when getting ready for a night dive, do you have a primary torch, a backup and a chemical light? Are they all charged fully? If prepping for a nitrox dive, have you made sure to calibrate your computer to your new air mix? Being sufficiently prepared is the key to safe diving.

4. Dive within your limits

Above all, remember that diving should be fun. Never put yourself in an uncomfortable situation. If you aren’t physically or mentally capable of a dive, call it. It’s easy to succumb to peer pressure, but you must always decide for yourself whether to dive. Don’t be afraid to cancel a dive or change a location if you feel that the conditions are unsafe that day. The same site may be within your capabilities one day and not the next, depending on fluctuations in surface conditions, temperature and current. Never attempt a dive that is beyond your qualification level — wreck penetrations, deep dives, diving in overhead environments and diving with enriched air all require specific training.

5. Stay physically fit

Diving is deceptively physically demanding; although much of our time underwater is relaxing, long surface swims, diving in strong current, carrying gear and exposure to extreme weather all combine to make diving a strenuous activity. Maintaining an acceptable level of personal fitness is key to diving safely. Lack of fitness leads to overexertion, which can in turn lead to faster air consumption, panic and any number of resulting accidents.

Obesity, alcohol and tobacco use and tiredness all increase an individual’s susceptibility to decompression sickness, while 25 percent of diver deaths are caused by pre-existing diseases that should have excluded the person from diving in the first place. Always be honest on medical questionnaires and seek the advice of a physician as to whether or not you can dive. Be mindful of temporary impediments to physical fitness — while a cold may not be dangerous on land, it can cause serious damage underwater. Recover fully from any illness or surgery before getting back in the water.

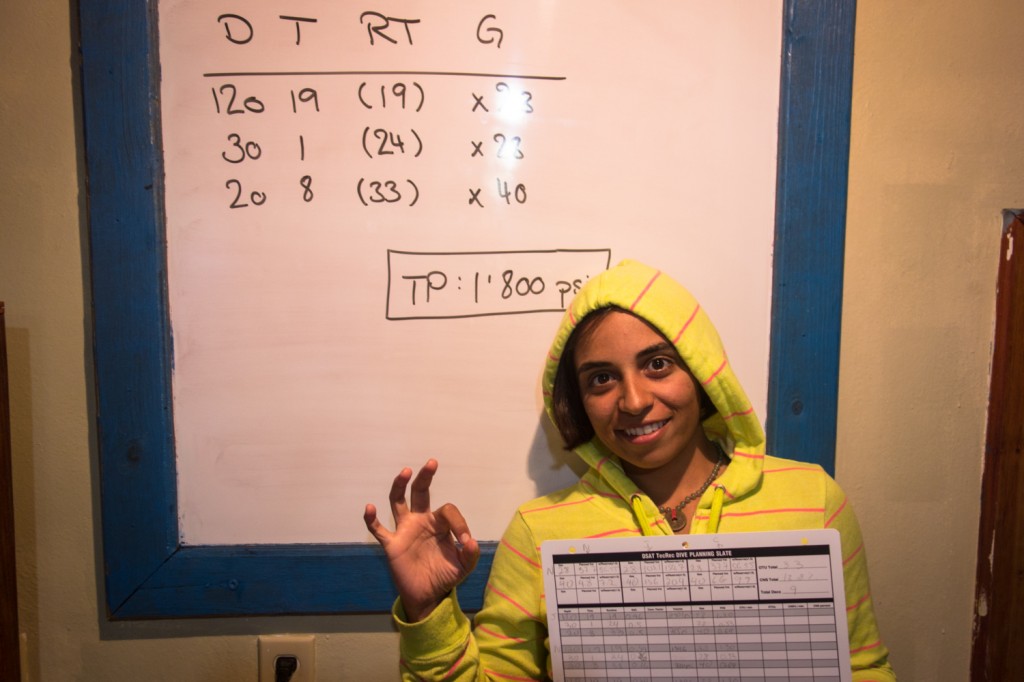

6. Plan your dive; dive your plan

Taking the time to properly plan your dive is an important part of ensuring your safety underwater. No matter who you’re diving with, make sure that you have agreed on a maximum time and depth before submerging. Be aware of emergency and lost-diver procedures. These may differ slightly from place to place and depend upon the specifics of the dive. If you are diving without a guide, make sure you know how you’ll navigate the site beforehand. Make sure you’re equipped to find your way back to your exit point.

Communicate with your buddy, making sure that you are both agreed on the hand signals you will use; often, we’re paired with strangers while diving and signals can differ quite drastically depending on a diver’s origin. For example, the signal used for ½-tank of air in Asia and the Caribbean is the same signal used by divers in Africa to call the end of a dive. Sticking to your plan is as important as original planning. Check your gauges frequently throughout the dive. It’s easy to lose track of time, and suddenly find yourself dangerously low on air or several minutes into decompression. According to the diver fatality statistics provided by DAN, insufficient gas supply was the leading cause of fatal emergency ascents for the deaths analyzed, which could easily have been avoided if air supply had been properly monitored.

7. Rule of thirds

Apply the rule of thirds to air-supply management. According to this rule, a diver should designate a third of his or her air supply for the outward journey, a third for the return journey, and the final third as a safety reserve. This is a good rule of thumb, but must be adapted to situations that don’t fit the out-and-back profile, such as drift dives, where the entry and exit point are not in the same place.

Essentially, you should always factor a margin that leaves enough air for a slow ascent and a safety stop. Think not only of your own requirements but also of your buddy’s. Will you have enough air in your tank to donate all the way to the surface should an emergency situation arise? When planning a deep dive, end the dive with more air in your cylinder than you would when staying shallow to accommodate a longer ascent time. Similarly, when planning a dive in strenuous conditions like strong currents or cold temperatures, be aware that your air consumption will probably accelerate considerably.

8. Use the buddy system

Although several training organizations now offer solo diving certifications, diving alone remains an absolute no-no unless properly trained. The old adage “when you dive alone, you die alone” exists for a reason. The majority of emergency skills rely on the presence of a buddy. For example, without the possibility of an alternate air source in an out-of-air situation, you have very few options. You can perform a CESA if you are shallow enough. But in most cases, you would have to resort to an uncontrolled buoyant ascent, which would likely have severe physical repercussions.

Statistics from DAN, BSAC and DAN Australia showed that in 86 percent of fatal cases, the diver was alone when they died. Straying too far from your buddy or losing them completely can be a fatal mistake. Your buddy is your lifeline and support system underwater, and you should treat them as such. If the dive guide pairs you with a stranger before a dive, take the time to get to know them. Ask about their training and experience, and any special concerns they might have. For example, if your buddy wears contacts they will not be able to open their eyes underwater. You’ll need to assist them if they lose their mask. Always err on the side of caution when comparing gauges or computers with your buddy. Abide by the rules of the most conservative instrument.

9. Practice vital skills

Too often, divers allow the skills that they learn in their entry-level course to lapse over time. In some cases they never properly mastered the skills in the first place. Poor instructors may have overlooked skills due to a large class sizes or a fluke performance at the time. These basic skills are vital to diver safety. Being able to capably perform them in an emergency could be the difference between life and death. Knowing how to use your buddy’s alternate air source, how to conduct a CESA, and how to disconnect your pressure inflator hose are all vital skills in many emergency situations.

Other skills are important in a preventative rather than a reactionary sense. Good buoyancy control is key to avoiding dangerous uncontrolled ascents. Mastering mask clearing could one day be the difference between calmly addressing a problem and succumbing to panic. Rescue-certified or equivalent divers are in a position of responsibility. At any moment, they may need to perform CPR, remove a diver from the water, or give emergency oxygen. Practice and refresh your skill set frequently. Make sure that you’re confident you know how to act if something goes wrong.

10. Establish positive buoyancy at the surface

We usually think of dangerous diving situations occurring underwater. But in reality, 25 percent of diver fatalities stem from problems that arise on the surface. Fatigue is a factor in 28 percent of diver deaths. This is most commonly due to a diver attempting to remain on the surface while over-weighted. Establishing positive buoyancy at the surface conserves energy, preventing exhaustion and drowning. You should establish positive buoyancy at the end of every dive. Doing so is the first step in providing assistance to a tired, panicked or unconscious diver at the surface. Inflate your BCD fully, and if necessary, drop your weights.

Staying safe while diving is simple. With careful preparation, common sense and skill confidence, the potential risks are effectively minimized. Following these rules and the other guidelines of your training not only keeps you safe, but also allows you to relax and have fun. And that, after all, is why you go diving in the first place.