By Samantha Craven, Project Manager, The Reef World Foundation

Have you felt a difference in your climate lately? Noticed unpredictable weather patterns? Longer, hotter summers? Well, corals have felt it too. Over the last year, marine scientists, conservationists and divers worldwide have worried about the current global coral bleaching event. Temperature stress is one of the main culprits behind coral bleaching, and as both climate change in general and El Niño events drive sea-surface temperatures ever higher, our corals are facing their biggest challenges ever. The outlook is terrifying, but there is a lot that divers can do to keep hope for coral reefs alive. The first step is becoming better educated about the bleaching threats facing coral reefs.

Stressed Out

Corals are sensitive animals, and anything outside of their normal environment or comfort zone causes them great physical stress. We mostly associate bleaching with temperature stress, when the surrounding waters are higher or lower than their optimum range, 68 to 89 F (20 to 32 C). Pollution, sedimentation, disease and physical impacts like a touch from a diver can stress them out too.

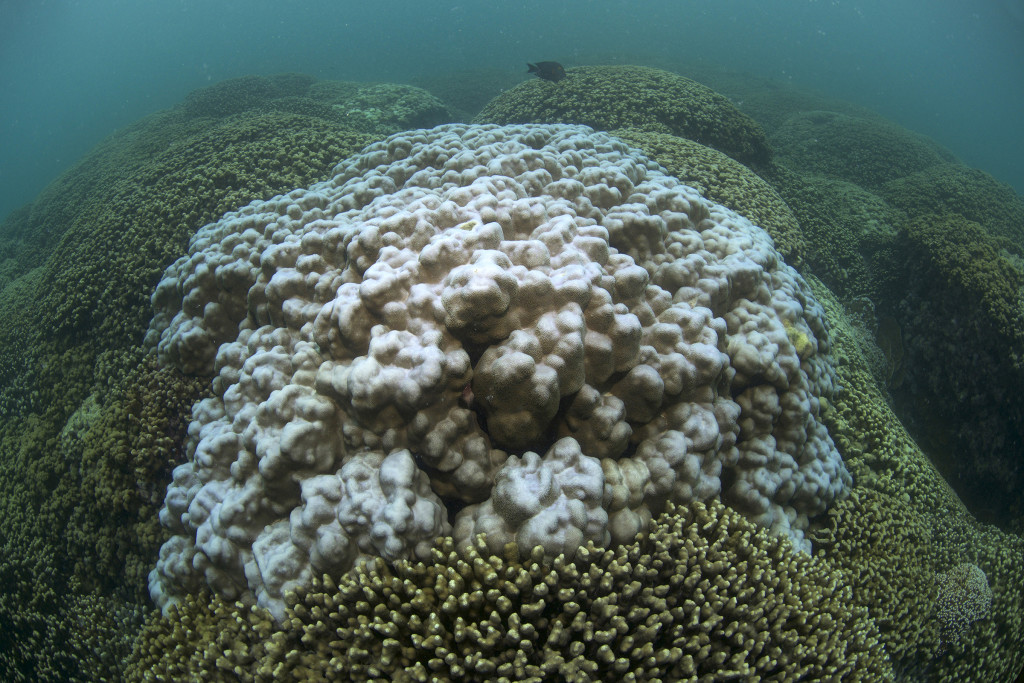

When corals become too stressed, their mutually beneficial relationship with photosynthetic algae (zooxanthellae), which lives in their tissues, gets a bit rocky. Zooxanthellae provide coral with their rich colors and 80 percent of their nutritional requirements. If conditions become too hot or too environmentally stressful in another way, the coral will expel the zooxanthellae. Without these algae, the coral polyp is transparent and we can see its white calcium-carbonate skeleton, which is what we mean when we say a coral is “bleached.

When you see bright-white corals, the coral animal is still alive, albeit on an extreme diet. The food it catches on its own is only 20 percent of what it needs. If the stress is removed in time, coral will accept zooxanthellae back into their tissues and get on with life as normal. But if the stress goes on too long, the coral will die, and the skeleton will become overgrown with visible, fleshy algae. This type of algae covers any spaces new coral recruits could land, so there is no replenishment of live coral. Once this pattern has taken hold, we start to see an ecological shift from coral to algae-dominated reefs that house much lower biodiversity.

Global Problems

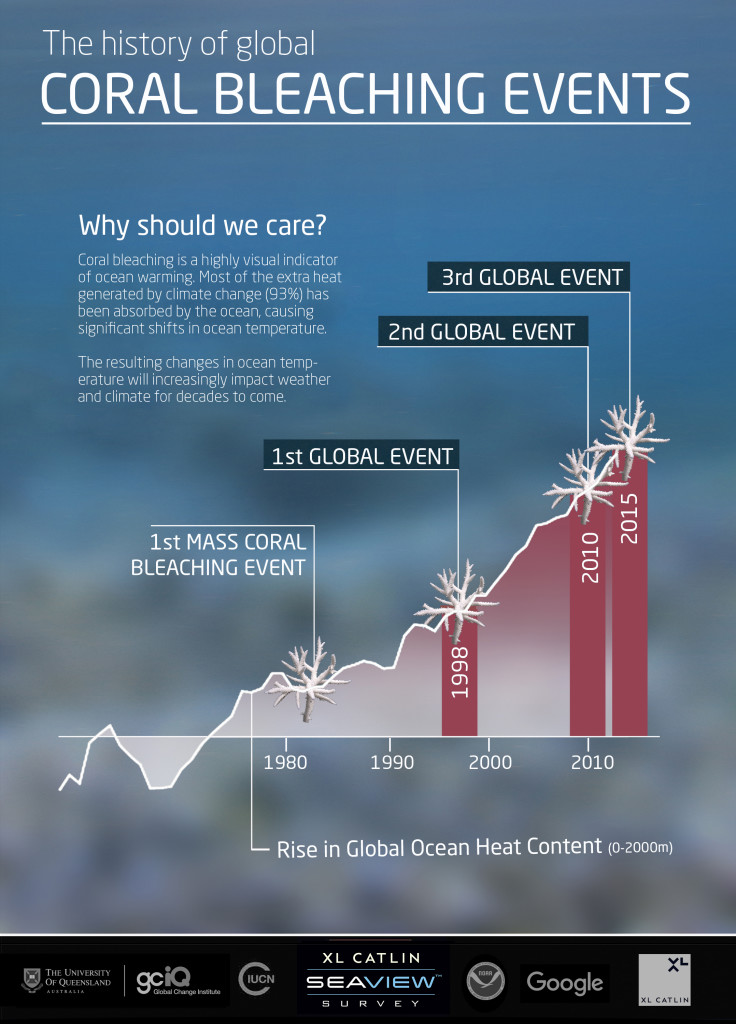

Mass coral bleaching occurs when corals bleach on a regional or global scale; there have been 60 recorded events between 1979 and 1990. Global coral bleaching events are the worst, defined as mass-bleaching events in all three tropical ocean basins — the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. There have only been two global coral-bleaching events in recorded history. In 2015, scientists confirmed that we’re experiencing the third at a severity heretofore unseen.

The first global coral bleaching event, from 1997 to 1998, caused at least 15 percent of global reefs to die. In 2010, it was a little less severe. However, the 2015 to 2016 event is predicted to impact up to 38 percent of the world’s reefs. Devastating images have come out of the Caribbean and Eastern Pacific so far and, as El Niño continues to grow into potentially the strongest-ever recorded event, the worst may be yet to come.

The outlooks for the Western Pacific, Coral Triangle and Indian Ocean are bleak, and new footage has just emerged from the Great Barrier Reef. This doesn’t just bode badly for the diver’s love of the aesthetically pleasing reefs, but also for the millions of people who rely on this ecosystem, which provides food, coastal protection and tourism income, and even supports life that makes the air we breathe.

Despite its widespread effects, we still understand very little about bleaching or a reef’s ability to withstand such stress. Why do some species bleach but not others? Why are some reefs annihilated while others recover? Paying heed to lessons learned from the two previous bleaching events, where we were caught unprepared, scientists are keeping close tabs on the current event, which is set to last at least for the rest of 2016.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Coral Reef Watch program has a wealth of resources to help scientists focus their efforts. Using years of satellite data about the surface conditions of the sea, they can see what parts of the ocean are experiencing warmer temperatures than the same weeks in previous years, and work out the severity of the risk of coral bleaching. Anyone can access these predictions and use them to manage how they use the reef.

What can you do?

There are two main avenues through which divers can be part of the solution; the first is to no longer be part of the problem. Remember that many things can stress corals, including direct damage from divers, anchors, and sunscreen, to name a few. The more stresses the coral animal has to juggle, the less resilient it will be to the big problems, like mass bleaching. You can help the resilience of reefs by ensuring that your diving behavior has the least impact possible. Don’t touch or kick anything, and choose operators with sustainable practices, as well as ones that don’t use anchors, such as Green Fins members.

The second is to be a citizen scientist. The more we know about bleaching, the better we can manage its impacts. You can be part of the global data-collection team, with a range of options to report bleaching sightings:

- NOAA has a clear and comprehensive survey for you to fill out, wherever you are in the world.

- Reef Check Malaysia is collecting bleaching data to help it mobilize teams to badly affected areas, but is interested in data from other regions as well.

- Green Fins Thailand, in conjunction with the Phuket Marine Biological Center, is calling for reports.

This is a critical year for corals around the world, but as scary as the numbers are, we can still make a difference. Even with the prediction that 38 percent of reefs will be impacted by the current global coral bleaching event, we can still do our part to help them survive. It all boils down to resilience — the corals’ capacity to recover from this challenge. Scientists think that removing local stressors may be the reefs’ best chance in the face of these global threats.

Every choice you make on your dive vacation counts, from choosing your operator to making sure your gauges are tucked away, to staying clear of the reef at all times and tipping the guide who holds you while you take a photo so you don’t cause any damage. And when it comes to the seemingly intractable problem of global warming as a whole, remember — individual, day-to-day choices matter too. Eat less fish and meat, if any. Say no to unnecessary plastics. Bike more, drive less.

These may seem like small actions to deal with enormous threats, but your choices are no small thing. Tourism is one of the fastest growing industries globally, and each time someone makes choices to lessen his or her personal impact, either at home or away, it makes a difference.