The Vamar is more than an average shipwreck. The site is not only one of Florida’s Underwater Archaeological Preserves and part of the Florida Panhandle Shipwreck Trail, but is also the scene of mystery and intrigue. When divers visit the site, they are swimming over history. During Vamar’s career, it was ia gunboat, a rum runner, a polar-exploration vessel and, finally, a tramp steamer.

History of the Vamar

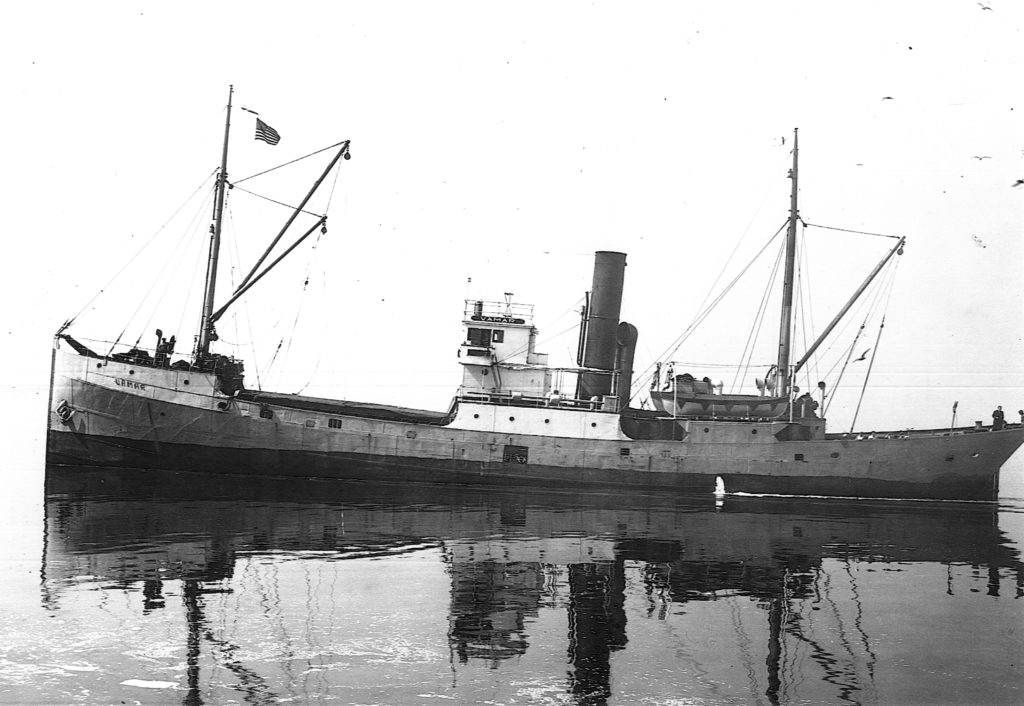

Launched in 1919, Vamar was originally named Kilmarnock, a patrol gunboat of the Kil class. Built by Smiths Dock Company of Middleboro, England, the ship was 170 feet long and 30 feet wide. It was registered at 598 gross tons. Renamed Chelsea after being sold to a private company, the U.S. government confiscated the ship while it was running liquor during Prohibition. In 1928, Admiral Richard E. Byrd bought the freighter at auction and used it in an expedition to Antarctica. His primary vessel was a Norwegian sealer, wooden hulled and built for polar ice, but he needed a vessel with enough space to carry airplanes for Antarctic exploration. He reinforced Chelsea’s bow to handle the ice and renamed it Eleanor Bolling after his mother. After a rough trip around Cape Horn, the crew nicknamed the ship “Evermore Rolling.”

The Eleanor Bolling’s time in Antarctica was a grand adventure. The ship nearly sank when a chunk of ice almost capsized it. Men went into the water but shipmates, including Admiral Byrd himself, jumped into the frigid sea to rescue them. Eleanor Bolling made several trips ferrying supplies from New Zealand to support the successful expedition, and was part of Byrd’s triumphant return to New York in 1930.

Becoming the Vamar

The vessel was considered unseaworthy for another expedition and sold to a sealing company, and then to a shipping concern. Renamed Vamar, it became a tramp freighter for the Bolivar-Atlantic Navigation Company, and fell into disrepair. According to a 1942 Coast Guard incident report, on March 21, 1942, Vamar left Port St. Joe, Florida, with a mixed crew of Spanish, Cuban, and Yugoslavian mariners and sank under mysterious circumstances. This was during the first months of American involvement in World War II, when U-boats were picking off Allied ships at an alarming rate.

Afterward, Coast Guard intelligence officers conducted numerous interviews and uncovered a strange story. The freighter sank on a straightaway, and the locals heard peculiar metallic banging noises coming from the ship the night before its final voyage. Locals also commented that the crew spoke in hushed tones, in foreign languages, at a nearby nightclub. They appeared flush with cash, and were seen in the company of a mysterious blonde woman. The townsfolk suspected the crew of sabotage, but the Coast Guard inquiry found no solid evidence for it.

The Vamar today

With the bow pointed south, the 170-foot-long freighter is now a jumble of scrambled wreckage. Vamar offers plenty of structure for divers to explore. Divers will see hull plates, deck beams, chain and a capstan. The steam engine and the generator that once powered the freighter are also on view. At the stern, divers will note a rudder and rudder shaft. There’s also plenty of marine life on the ship, including coral growth, snapper, grouper, amberjack and Spanish mackerel. Visitors might also see southern stingrays and toadfish.

Daly’s Dock and Dive in Port St. Joe is the local expert on Vamar, having visited the site countless times, and offers excellent guides. The wreck is perfect for beginners, since it sits in only about 25 feet of water. “Every dive on the Vamar has something new to see,” says Ann Marie Daly. “No matter how many times I’ve dived there, I always burn almost my entire tank exploring within and around the wreck.” Holly Waters, also of Daly’s, adds that the shipwreck “has quite the welcoming party as well, the resident Goliath grouper or nurse shark is usually found roaming around.”

A member of the public or an organization chose or nominated each of Florida’s 12 underwater archaeological preserves, also known as Museums in the Sea. Captain Daniel Beck of Mexico Beach nominated the Vamar in 2002, and, like all of Florida’s historic shipwrecks, it is protected by law. Please safeguard the site for future generations by taking only photos and leaving only bubbles.

By guest author Franklin H. Price, archaeologist with the Florida Department of State