If you’re looking for a shipwreck with a fascinating history near Panama City, Florida, it’s time to visit SS Tarpon. This late 19th-century steamship is one of Florida’s 12 Underwater Archaeological Preserves. SS Tarpon is an oasis of marine life. It also offers great lobster fishing and has a fascinating tale concerning its final voyage at sea.

The history of the SS Tarpon

Originally christened Naugatuck, the ship was built in Delaware in 1887. The ship originally provided freight and passenger service along the Naugatuck and Housatonic Rivers to New York City. It was 130 feet (39 m) long with a 26-foot (8 m) beam, and powered by twin-compound fore-and-aft steam engines and twin iron propellers. Naugatuck had auxiliary masts and sails in case of machinery failure and could sail when wind and sea conditions were favorable.

Henry B. Plant bought the Naugatuck after only two years because it could not compete with local railroad networks in the north. Rechristened SS Tarpon, the steamer helped expand rail operations in Tampa, Florida by carrying merchandise and building materials across the sea. In 1902, the Pensacola, St. Andrews & Gulf Steamship Company purchased the SS Tarpon, and it began weekly runs to the ports of Mobile, Pensacola, Saint Andrews Bay (Panama City), Apalachicola, and Carrabelle.

The SS Tarpon sinks

SS Tarpon’s final journey began in Mobile at the end of August 1937, when it was carrying 200 tons of general cargo for a trip east. After leaving Mobile, it made port in Pensacola. Here it took on a quantity of iron in addition to its previously loaded cargo of flour, sugar, canned goods, and beer. It was also over capacity with 31 people onboard. With 200 barrels of fuel oil in the tanks and 15 tons of freshwater, SS Tarpon’s decks were awash when it departed port on the evening of August 31, 1937 for Panama City.

The weather began to turn and the ship took on water from a leak at the bow, made worse by rough seas. It began to list to port as the crew worked to pump water from the bilge. To counter the listing, they jettisoned barrels of flour, which helped to right the ship. Conditions worsened, however, and when winds reached gale force, SS Tarpon took on more water through the bulkheads and listed to starboard. Again, the crew jettisoned cargo, but they could not right the ship. They diverted from their course while trying to beach the steamboat before it sank. Captain Barrow ordered more cargo jettisoned and was adamant that they return to their original course, but the ship had already begun to sink. By the time the captain issued the order to abandon ship, the stern had settled into the sea.

Loss of life

Mounted on the boat deck were three standard lifeboats and one work boat for a total carrying capacity of 61 people. The crew successfully launched only one boat, which capsized with the cook’s wife onboard. A falling boom killed the second mate, and Captain Barrow himself drowned after washing overboard. Other crewmen floated near the wreckage on debris. When the weather cleared, the ship’s oiler sighted land and decided to swim to shore for help. By 10 o’clock the next morning, he reached Philips Inlet, west of Panama City, after spending 25 hours in the water.

A passing motorist on the Gulf Coast Highway picked up the survivor and drove him to Panama City to report the disaster. News of SS Tarpon’s sinking quickly spread. The Coast Guard dispatched a search plane and two cutters, rescuing 11 men from the water. One survivor made it to shore on his own. The Coast Guard recovered two bodies, one of them Captain Barrow. Some of the crewmen were found, and it’s thought that they were trapped in the cargo hold and drowned when the ship sank. In total 18 people died, although some were never identified. After an inquiry by the Bureau of Marine Investigation and Navigation, Captain Barrow received full blame for attempting to keep the ship on course in terrible weather while it was heavily loaded with cargo.

Diving on the SS Tarpon

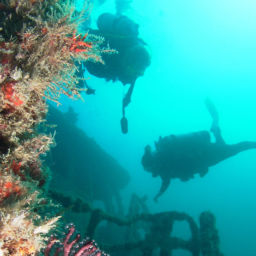

Today, the 160-foot (48 m) wreck lays at a depth of 90 feet (27 m), 7.8 nautical miles from shore. The Coast Guard marked the location in 1939, and that’s where local fishermen in the 1940s and scuba divers in the 1950s located the sunken steamer. Early divers could swim through the cargo hatches and into the hold, where stacked cases of beer still sat.

After years underwater the wreck is much changed. The hull has given way, and much of it has flattened over the surface of the seabed. Only the hard pan bottom keeps it from sinking into the sand. Prominent features include an anchor winch, boiler and boiler bed, iron hull plates, winch assembly with wire cable, propellers, and the remains of the twin engines and donkey boilers. The wreckage is home to hard corals, crustaceans, jellies, amberjacks, grunts, and sharks. Visibility is decent, although it can become murky after rainfall. Watch for the large concrete monument that designates the wreck as Florida’s sixth Underwater Archaeological Preserve.

Diver’s Den in Panama City Beach has this to say about the wreck: “The Tarpon is one of our favorite dive sites here at the shop. The history behind the wreck and the natural hard bottom around the site make for great conversation and amazing dives. It’s fascinating for our divers to visit a wreck that was built in 1887 and sunk in 1937. Almost 80 years later, there are still sections of the ship that remain and are home to a vast array of marine life that our divers look forward to seeing year after year.”

Many local dive shops have informational brochures about SS Tarpon as well. Divers should remember that shipwrecks are nonrenewable resources, and must be protected for future generations.