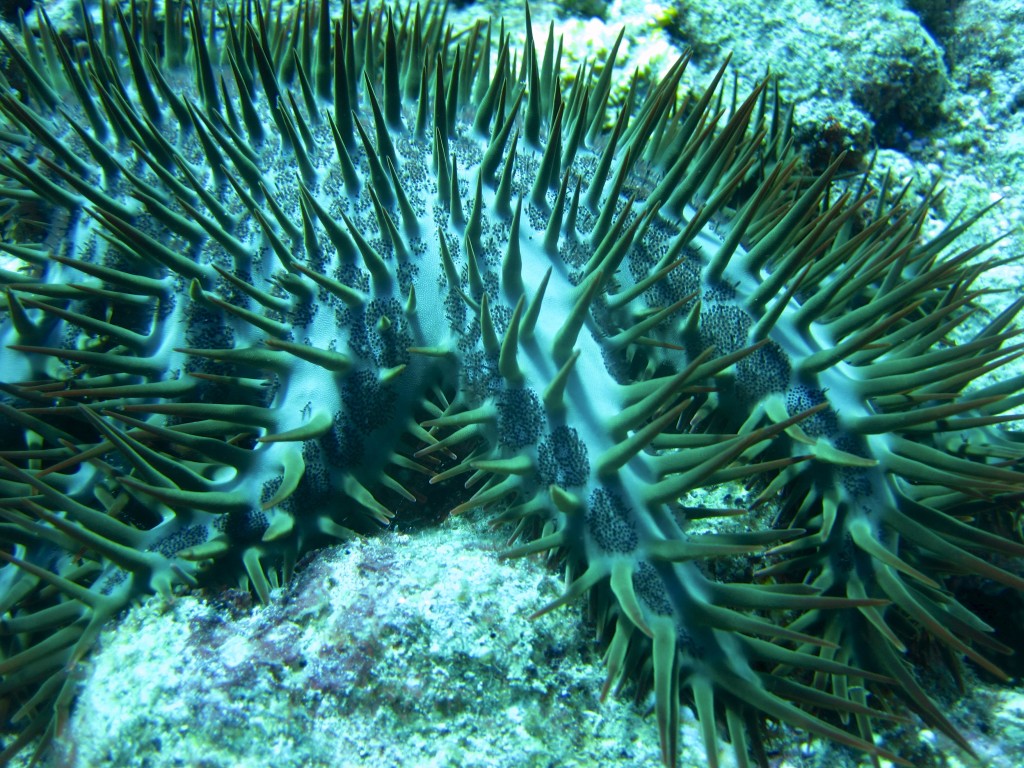

Imagine you’re a subaquatic rock star with 21 arms, covered in row upon row of wicked Technicolor spines. Your only predator is a snail called Triton’s trumpet, a mollusk with a shell so pretty that those grabby humans can’t keep their larcenous little fingers to themselves. You’re laughing all the way to the reef while the only animal that can slow your roll is dragged off as a sacrificial offering to the God of Exotic Vacation Souvenirs. It’s time for a celebratory feast, so you settle down to suck some serious polyps as the coral cowers before you in mortal terror. You’re ravenous. You’re unstoppable. You are Acanthaster planci: The crown-of-thorns starfish — or COTS, to your friends.

For divers, a front-row ticket for a crown-of-thorns starfish sighting is pretty memorable. A thousand whimsical reef fish might flutter by, tripping along to the flutes of a light symphony. Then suddenly there’s this crown-of-thorns, huge and benthic and dangerous, to inject a discordant note of pure metal. On a regular day out you might see a few loners skulking around the reef, chowing down on choice corals. Like any sea star worth its salt though, sometimes the crown-of-thorns starfish get rowdy and start causing trouble. And when a COTS party gets out of control, the consequences are a lot more serious than a wrecked hotel room. Sometimes an entire reef can pay the price.

In 1967 a huge bloom of crown-of-thorns starfish erupted over the Tanguisson Reef on the west coast of Guam. The result was an estimated 90 percent loss in coral coverage. Plenty of science still needs to be done before we fully understand all the factors that contribute to COTS population explosions, but when you’re as cool as these echinoderms, it’s hard to keep the groupers groupies at bay. The most likely suspects are a combination of the natural rhythms in the COTS’ reproductive cycle and an unexpected boon from those oblivious humans again. See, the runoff from human agricultural and urban activities leads to an increase in nutrients in the water, which means more phytoplankton for the larval COTS to gorge themselves on, and more thorny adults to get busy producing the next generation.

Juveniles are small, transparent, and pretty easy to push around. After practicing their predatory chops on all that phytoplankton, they start to hone their coral-devouring skills and bulk up, overwhelming the reef around them in a voracious legion. In recent years on Guam, there have been chronic, if less severe, outbreaks. These flare-ups change the ecosystem of the reef in ways that don’t just neatly reverse once the bloom ends.

To a reef, a COTS invasion is a bona fide natural disaster, leveling entire communities. For the stationary residents of the reef, there is no running. There’s nowhere to hide from a predator who can extrude its stomach and digest you where you sit, leaving behind only a bleached scar to show where you once had been. And sure, the corals can rebuild, but the old neighborhood won’t ever be the same. Opportunistic algae start sliming their way in, taking further advantage of the ravaged coral, and just when it seems safe to spawn and raise a few polyps, another crown-of-thorns starfish invasion tears through town and the whole process begins again.

But crown-of-thorns starfish get kind of a bad rap, too. Sure, they sport venomous spikes and dress a little flashy, and can overwhelm the carrying capacity of an ecosystem if left to reproduce unchecked…but what species among us wouldn’t breed out of control if given the environmental opportunity? Can we really fault them for that? Without at least a few of these colorful characters to stalk the reef, one or another particular type of coral could breed to excess, jostling for dominance. So a few COTS are actually integral to the overall health of the reef, it’s only in the case of a runaway population boom that the equilibrium of the ecosystem is threatened.

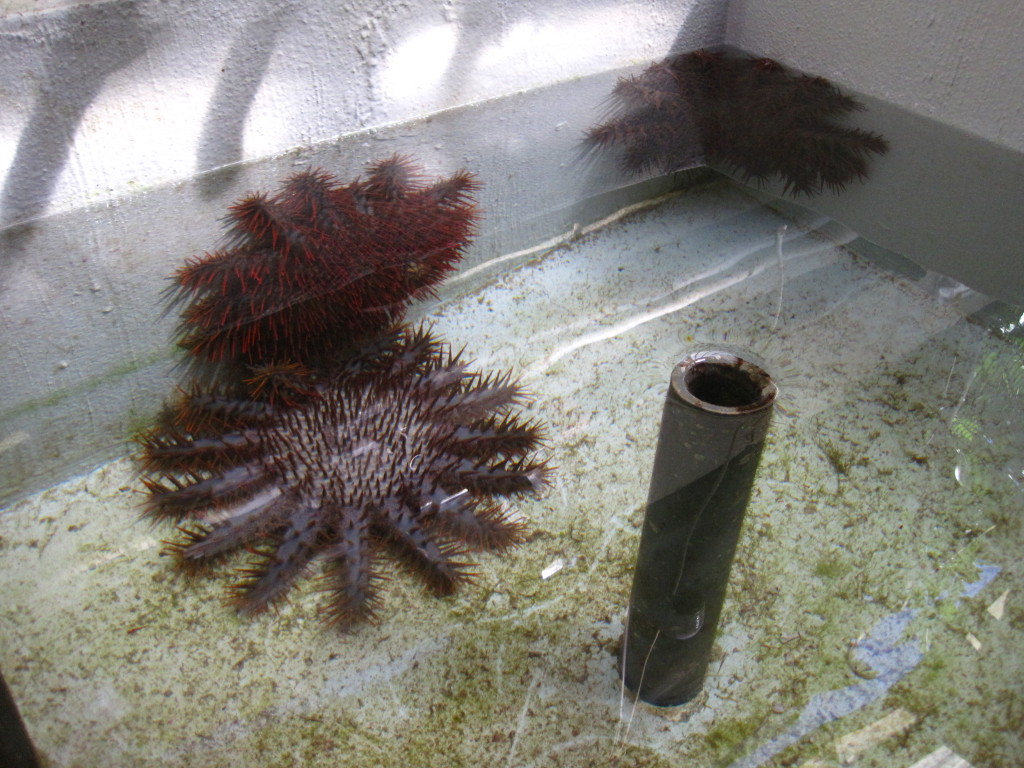

Here again, the humans want to get in on the action. In the case of the crown-of-thorns starfish, they started a campaign to kill and dismember on sight. But COTS laugh in the face of death, and will only regenerate each severed piece into an insatiable new mouth unless you dismantle them into at least eight separate pieces. Determined divers have found ways around this, sometimes coring out the eating, eliminating, and reproductive organs of the COTS. Some divers prefer to flip them off the reef with a fin tip and pin them under rocks to prevent them from crawling back. But in a stunning flash of poetic justice, scientists have discovered that the best way to fight a creature comprised of big needles full of toxic chemicals is… with a big needle full of toxic chemicals.

Sodium bisulfate is also known as dry acid, and it’s a fairly common household chemical used to maintain home swimming pools. When dissolved into a solution and introduced to a crown-of-thorns starfish through a syringe, it causes death and liquefaction within a couple of days. It’s a gruesome but effective way to go, as the animal morphs from a nearly invincible spiked predator to a washed-up mound of white slime and scattered needles. The problem is that there aren’t any comprehensive studies about what sodium bisulfate might do to the rest of the reef inhabitants, and accidentally poisoning the populations we’re trying to protect is a poor way to deal with a problem.

However, since biochemical warfare seems so promising for land wars, scientists developed an unlikely new strategy — fighting crown-of-thorns starfish with cows. Acanthaster vs. bovine in a submarine cage match to the death. Okay, not really. But concentrated salts derived from cattle bile are the next big things in quashing the starfish invasion. It seems to be a much healthier alternative for the safety of other reef denizens, but hardly less toxic to the COTS.

Ox gall, ox bile, or bile salts, as they are alternatively known, cause an immune reaction in the crown-of-thorns that causes them to break out in blisters, secrete mucus from their spines (before losing them altogether) and deteriorate into limp masses of necrotic tissue. It’s a real biblical plague of a solution, but it works, and it just may be the strategy that marine scientists have been seeking to thwart the destructive COTS blooms in places like Saipan and the Great Barrier Reef.

For those of you reading along at home, this is not a call to arms. Before you go on a buying spree for bile salts and syringes off the Internet, make sure that COTS are really a problem where you dive. Population explosions are a big deal and don’t do the reef any favors, but if you start a COTS genocide without doing your research first, you could wind up killing off the few mavericks necessary to keep things in balance. In short, you could become the next big threat in your misguided attempt to defend the reef, so it’s a better bet just to leave population management to the experts.

Randy and Jennetta at the Micronesian Divers Association shop in Piti, Guam urge you to educate yourself on the situation in your area before taking action. To drive the point home, they dusted off the old tale of the Caribbean Pterois volitans (red lionfish) another larger-than-life legend in the Invasive Species Hall of Fame.

The story goes that once upon a time in the Atlantic, some hard-core fans of the red lionfish realized those guys were just too wild to be tanked. So they liberated a pair of them from a home aquarium off the east coast of the US to roam the idyllic waters of the Tropic of Cancer like a piscine Adam and Eve. From the loins of that original pair a legion burst forth, devastating ecosystems from Florida to the Dominican Republic. Of course, that could all be just a big fish tale, but the fact remains that there are lionfish in the Caribbean and there shouldn’t be, so a lot of programs in the region encourage divers to kill first, ask questions never.

However you feel about this type of culling, it’s meant for a particular time, in a specific place. But not right now, and not in Guam. Yet the divers, they cull. They come to Guam with a bloodlust for the hapless lionfish, fueled by the righteous indignation of the eco-warrior. But you know where a road paved with good intentions leads…and this tragic tale ends with misguided divers slaying the fish in their native habitat. They drive the populations deep into the no-dive zone, evicting them from the warm Micronesian waters where they actually belong. This tears a hole right in the middle of the food chain, and means fewer of them to dazzle divers and poke the unwary. It goes to show how a little human ignorance can go a long way in damaging the health of an ecosystem.

So if the clarion call of COTS control does inspire you to action and you just have to do something about it, a great way to help is to report when you see unusually high concentrations. You can use the free Eye on the Reef app for GBR sightings or if you live in Guam, you can email local expert Ciemon Caballes of the University of Guam at [email protected]. For those crusaders seriously committed to COTS culling, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority has some guidelines for how to safely and legally wreak havoc on overzealous starfish populations here, complete with how-to videos and manuals. The best strategies combine knowledge of the area and comprehensive training.

“Outbreaks definitely need to be controlled, but management should be at the population level and not at the individual level,” said Caballes. “Divers can definitely help in organized control efforts (like in the 1960s here on Guam) as these are often labor-intensive.”

Most of us get into diving because we like to push boundaries, go places few others dare. It’s natural to want to defend the habitats of those organisms that make our aquatic frontiers so fantastical, but our first order of business as allies of the environment should be to take a look at our own impact before we start cutting down other species for their infractions. If we aren’t prepared to do what’s really right for the reef, it’s best if we admire from afar, star struck by the surreal glamor of ostentatious lionfish and the beautiful brutality of the crown-of-thorns. I think it was Hunter S. Thompson who said, “With a bit of luck, your life will be ruined. Always assume that just behind some round coral on all of your favorite reefs, COTS with impossible spines are getting incredible kicks from things you’ll never know.”*

Special thanks to Ciemon Caballes and Devin Resko at the University of Guam for the fantastic information on COTS and the tour around the U of G Marine Lab. Thanks also to Randy and Jennetta at MDA, and Felix Reyes at the Guam Visitors Bureau for their insight into the local COTS situation.

*Hunter S. Thompson absolutely did not say this.