I recently revisited the Thistlegorm, one of the world’s most famous wrecks, and one of the best dives in Egypt’s Red Sea. I did two dives there, one a survey of the wreck from the outside, and one where we swam inside, looking at the cargo of trucks, rifles, airplane parts and boots. And I may have been one of the last divers to do so, if Egypt’s Chamber of Diving and Watersports (CDWS) follows through on discussions of closing the wreck, or at least limiting access.

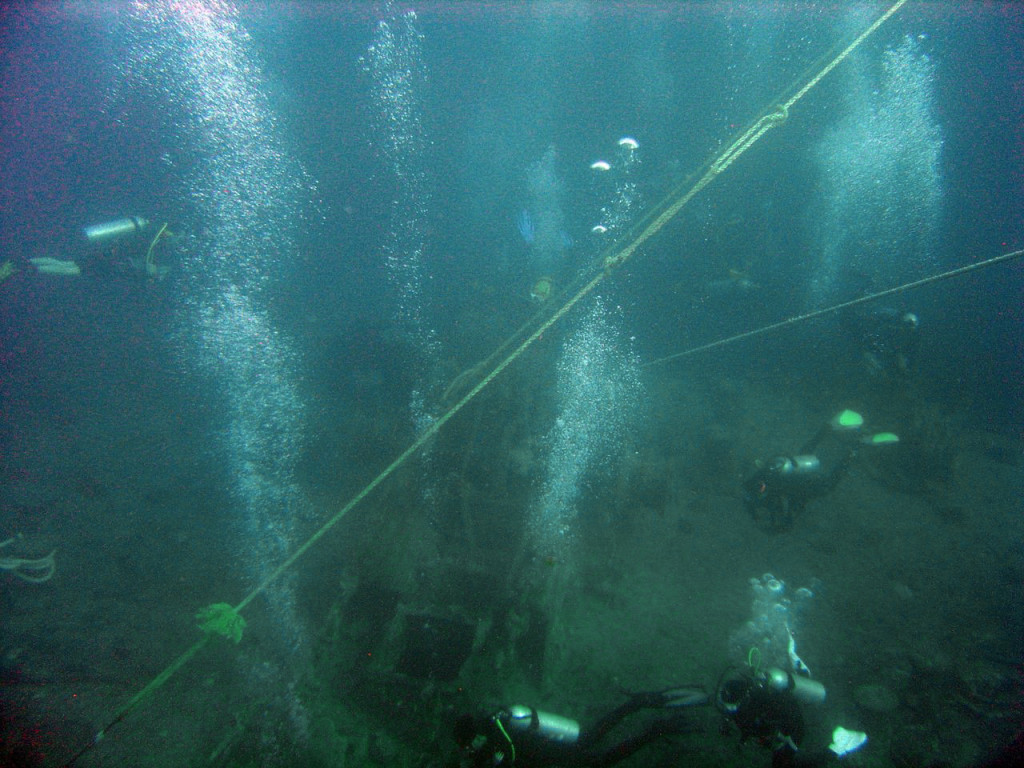

The problem is that the Thistlegorm is disintegrating, fast. We’re talking about a metal ship, submerged in saltwater for more than 60 years, so disintegration is inevitable, but Thistlegorm divers, at once its biggest admirers and worst enemies, are expediting the process at an alarming rate. Divers are not purposely destroying the wreck, nor is it careless finning, as is the case with a number of coral reefs around the world. The problem is one we cannot easily change: we breathe. Or, more specifically, we exhale, and as we do so, we send bubbles up through the water column. Under normal circumstances, these bubbles go straight to the surface and their contents mix with the surface air. But they are trapped inside a wreck. And since we don’t consume all the oxygen in the air we breathe, our exhalations actually contain a fair amount of oxygen. And oxygen is a prerequisite for corrosion, which is scientifically known as an oxygenation process. So when we introduce additional oxygen to metal or wood in salt water, we significantly speed up the process of breaking it down. Because of this, some of the most popular wrecks in the world may in time be closed off to penetration, or at least have limitations set on the number of divers that can enter. Another option would be to reserve penetration on these wrecks for divers with closed-circuit rebreathers, as they have no expelled air.

In any case, these measures will only delay a wreck’s complete disintegration. Within a few years all the wooden shipwrecks from the Age of Sail — of tall clippers, exploration, and pirates — will most likely be completely gone, devoured by the sea.

So should we close off wrecks to protect them? Or should we enjoy for them what they are for as long as they’re here? After all, a wreck is not like a reef. It is not a part of the natural balance of things; it is not something that has always been here, that we bumbling humans are destroying. The beauty and the lure of wrecks is their ephemeral nature; the experience is finite. When we dive a new, pristine wreck, we do so with the knowledge that one day, it will be gone, eaten by the sea that is its home.

Whatever the CDWS, or other governing bodies, decide on the future of endangered wrecks, as a diver, I will respect the decision. Until then, I will continue to dive the wrecks of the oceans, enjoying every moment of their decomposition. As I hope any diver on any wreck does.